On April 15, 2013, two homemade bombs exploded near the finish line at the Boston Marathon, killing three people and injuring more than 260. Although five years have passed, for Boston Globe photographer John Tlumacki, it “seems like yesterday.”

Before the explosions, Tlumacki described the day as “normal, like any other April day.” A staff photographer for 30 years, Tlumacki had been covering the marathon for two decades, which usually averages around 30,000 participants a year. He knew the best spot for photos was at the finish line.

That’s where he was on that “normal” April day when he heard the first explosion. Tlumacki ran toward the sound, thinking perhaps a manhole cover had blown off. But when a second explosion went off seconds later, he knew something bad was happening.

As he made it to the sidewalk, Tlumacki saw he was right. On the ground were dozens of bloody and injured spectators, many of them missing body parts. A police officer yelled at him to leave the area in case another bomb detonated but he didn’t move. For 15 minutes, he didn’t take his eye off the camera, documenting the chaos and confusion, but also snapping photos of people helping others. Looking back, Tlumacki said it was probably foolish of him to stay, but he feels he did the right thing.

“I had an obligation to stay there as a journalist,” he said, “to stay there and take photos.”

Tlumacki isn’t alone. For many journalists covering traumatic events, it’s that sense of obligation to do their job that makes them run toward danger rather than away from it. Along with police, firefighters and paramedics, journalists are often the first responders to a scene. And like first responders working traumatic events, they are at risk of showing psychological problems, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and substance abuse.

From natural disasters to mass shootings, journalists are reporting from disturbing situations that can take a massive physical and emotional toll on their health. But are newsrooms doing enough to take care of their journalists, or are we in danger of seeing them burn out and fade away?

Boston Globe photographer John Tlumacki became close with Celeste Corcoran and her daughter, Sydney, after the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. He spent a year documenting their recovery process. (Photo courtesy of John Tlumacki)

Boston Globe photographer John Tlumacki became close with Celeste Corcoran and her daughter, Sydney, after the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. He spent a year documenting their recovery process. (Photo courtesy of John Tlumacki)

Taking Care of Our Own

When Tlumacki returned to the newsroom and began looking through his photos, he was in disbelief. There are some photos, he said, that will never see the light of the day. These graphic images still appear in his dreams years later.

Although the Globe offered counseling, Tlumacki said he didn’t go, but he admits he could have benefitted from some PTSD counseling.

“I felt like since I was not injured and I didn’t lose anything, I didn’t have PTSD,” he said. “Now I know that was foolish of me to think. It was still difficult for me. For a few years, I refused to take pictures at the finish line. One time I was getting ready to give a lecture and someone had left a backpack in the back of the hall, and I started to get really sweaty. Sometimes I had feelings like that.”

What helped Tlumacki heal was spending a year photographing Celeste Corcoran and her daughter, Sydney, during their recovery process. Both women were hit with shrapnel during the explosions; Celeste lost both of her legs.

“That was the best thing I did,” Tlumacki said. “I think we both benefited from each other. It was remarkable watching them get better. Following them became a way for me to deal with what happened.”

As Tlumacki’s story shows us, there are some things journalists simply cannot anticipate. Such as the night of Oct. 1, 2017 when a gunman opened fire into a crowd at a music festival on the Las Vegas Strip.

According to Las Vegas Review-Journal deputy managing editor Peter Johnson, there were no journalists on scene covering the festival that night, and there was only a small crew working in the newsroom. That changed when Johnson heard on his police scanner at home that there was an active shooter on the Strip.

Peter Johnson

Peter Johnson

“Our police reporter was dispatched, along with ten other reporters, and some photographers headed there on their own,” he said. “We didn’t really know what was happening since there were reports of multiple shooters at multiple locations. But we knew we were sending them into a potentially dangerous situation, which weighs heavily on you. These are our friends and colleagues and we care about them. We hoped they’d get the story and prayed they’d come back safe.”

Johnson described the night as “surreal.”

“The first word was that there were two dead, then 20 dead, then 50 dead,” he said. “Suddenly your jaw drops. It was a completely numbing number.”

At the scene, photographers transmitted hundreds of photos back to the newsroom. “Very disturbing photos,” Johnson said. “It was upsetting for everyone.”

When it was over, the Las Vegas incident became the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history with 58 people killed and more than 500 others wounded.

“We’re not a very large newsroom,” Johnson said. “So everyone was involved with covering it, and everyone was affected by it in some way. This was our community.”

Johnson said a therapist came into the newsroom that first week and journalists were encouraged to go in and talk. Several of them did, according to Johnson. Therapy dogs were also brought in to help.

Nearly a year later, the newsroom continues to report on the shooting’s aftermath. Recently, the paper released several batches of videos from that night captured on police body cams and surveillance cameras. But Johnson knew for some reporters, it would be troubling to relive it.

“We asked for volunteers to watch them,” Johnson said. “And if you were uncomfortable, you didn’t have to.”

He said several staff members are still haunted by what they saw that night, but what Johnson has learned is “we need to take care of our own, look after our people and realize the impact that happens to them when they’re reporting on mayhem.”

Julie Anderson also knows what it’s like to report on mayhem. Two weeks after a former student opened fire at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. on Feb. 14, Anderson started as editor-in-chief at the South Florida Sun Sentinel. She previously served as senior vice president of content and business development for the Orlando Sentinel Media Group, where she oversaw coverage of the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016.

Coming into her new position, Anderson said the first thing she wondered about was how everyone was going to handle the situation.

Julie Anderson

Julie Anderson

“Because you’re running on adrenaline, you’re not thinking of yourself, you’re living and breathing the story,” Anderson said. “Sooner or later, it’s going to hit you.”

Not only the fatigue and stress from working long hours, but the emotional turmoil that follows after speaking with survivors and the loved ones of victims.

“In Orlando, we had to write forty-nine obits,” Anderson said.

She said free mental assistance was offered, therapy dogs were brought in and employees were encouraged to take time off. The abundance of support from newsrooms around the country also helped. Newsrooms in Boston, San Bernardino and Charleston (cities who experienced their own tragedies) sent notes and meals to them, said Anderson. And when the next school shooting occurred in May in Santa Fe, Texas, the Sun Sentinel paid it forward and reached out to the local newspaper, the Galveston County Daily News, right away.

For some journalists in Orlando, it was their second time covering a massacre. “They had covered either Sandy Hook or Aurora,” Anderson said. “Some of them have left the business because they don’t want to be sad anymore. I worry about that.”

For Colleen Wright, it was the destruction of Mother Nature that sent her newsroom into high alert. Wright was a reporter for the Tampa Bay Times when Hurricane Irma struck last September. Irma, a Category 5 storm, was the most intense hurricane to hit the U.S. since Katrina in 2005. Although Wright was born and raised in Miami (where she is currently the Miami Herald education reporter), it was her first time covering a storm; it was also her first time taking shelter. Wright spent two nights at St. Petersburg High School, but that didn’t stop her from doing her job. Since she covered schools, she wrote about life from inside the shelters, and spent time driving around talking to people preparing to evacuate.

“We were on hurricane watch a week before the storm even hit,” Wright said, calling it one of the longest weeks ever. “It was all hands on deck.”

Although the damage to the area wasn’t as severe as other parts of the state, Wright said it was still physically exhausting to work those long hours, but she was proud of the work her paper did.

“It was okay to relax and say good job,” Wright said. “There will be another storm, and we will always be prepared.”

A month later on the other side of the country, the Tubbs fire became one of the deadliest wildfire in California history. The fire affected Sonoma and Napa counties in Northern California, destroying more than 5,000 structures and claiming 40 lives.

Like Wright, Santa Rosa Press Democrat photographer Kent Porter spent a week monitoring the weather with “one eye open.” The night the fires started, he heard reports on his police scanner at home and immediately grabbed his equipment to go do his job.

When he arrived on scene to take photos, a firefighter told him, “This is the kind of fire that kills people.” But this wasn’t Porter’s “first rodeo” as he put it.

Porter quickly sent pictures and videos back to the newsroom and warned his managing editor, Ted Appel, that the fire was heading to Santa Rosa. Appel updated the paper’s website shortly, and thanks to the work of reporters and Porter’s photos and videos, they were able to keep the public up to date. Their coverage landed them a Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Reporting this year. But Porter wasn’t looking for awards that night he set out with his camera.

“You lay yourself out there on the line because no one else can tell the story,” he said.

Although Porter didn’t lose his home, many of his friends did. “It was hard to comprehend that this was happening in our own backyard.”

There was also an “overwhelming sense of anger, grief, depression and anxiety”

for the photographer. He recalled taking a helicopter ride after the fire to take photos of the destruction. What he saw below made him “lose it.”

Afterward, the company allowed reporters to take time off, but Porter recommended newsrooms gather together after covering a traumatic event to debrief. “Sit as group and just talk about your experiences,” he said.

To help him slow down, he turns off his police scanner at home, listens to music and spends time with his wife. But when the next round of fires comes, Porter said he will be ready because it’s his job to show people what he sees.

“They need to know,” he said. “They deserve to know.”

Support and Solutions

When a gunman killed five employees at the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Md. on June 28, it became the deadliest assault on journalists in the United States since 9/11. Immediately, newsrooms around the country began to reassess their safety and security.

GJS (Global Journalists Security) was created in 2012. The company specializes in safety training for journalists, NGO professionals and other civilians operating in moderate and high-risk environments. Training programs include sexual assault awareness, emotional self-care and digital safety.

GJS executive director Frank Smyth believes safety training is critical for newsrooms, but he acknowledges most local news organizations cannot afford them. To those newsrooms, he offered these tips instead. “Install bullet-resistant doors and windows. Put in security cameras. Control access on who comes in and out of your building. Train your employees to be aware of their surroundings when they’re walking to their vehicles on the street or in a parking lot. Create a culture where everyone looks out for each other. The notion is to be smart.”

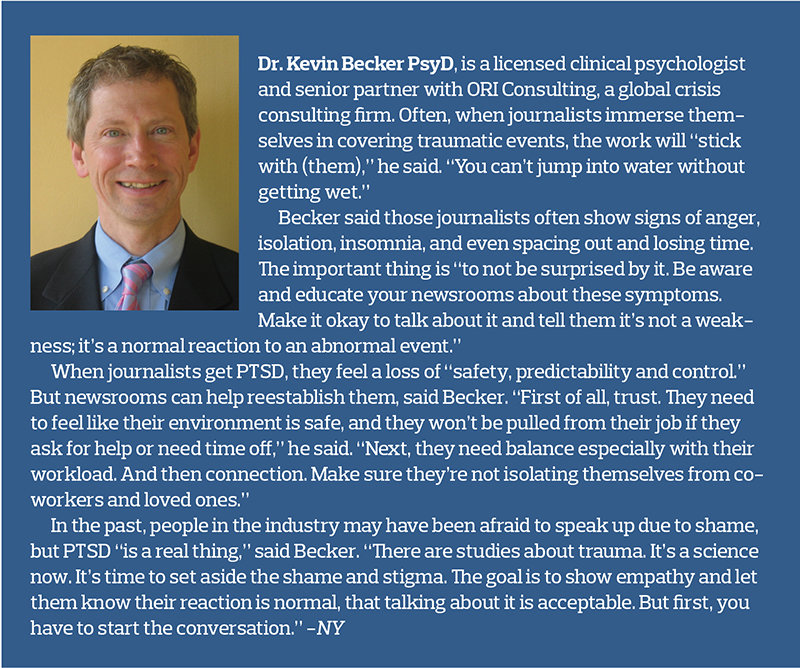

When the Dart Center started in 1999, the concept of PTSD with journalists was still relatively new. Journalists are known as a resilient group, said executive director Bruce Shapiro, but newsrooms began to realize reporters needed a better toolkit. The “steady diet” of traumatic events like mass shootings, hurricanes and the loss of colleagues has made it “overwhelming,” said Shaprio.

Bruce Shapiro

Bruce Shapiro

“We’ve reached a point where the industry is willing to have conversations about mental health and PTSD,” he said. “Local reporters and photographers are now on the frontline, and they need training because they’re not exempt from the trauma.”

Burnout and stress also factor into a journalist’s well-being; fortunately, there is a shift in newsroom culture. Shapiro considers it a generational turning point, where today’s younger reporters are much more open about talking trauma and its impact. He encouraged more journalists to form peer supported groups for community and help.

An example is the closed Facebook group Journalists Covering Trauma started by Orlando Sentinel reporter Naseem Miller and San Antonio Express-News reporter Silvia Foster-Frau.

Miller, who had covered Pulse, reached out to Foster-Frau after the deadly church shooting last November in Sutherland Springs, Texas that killed 26 people. After connecting, they decided to create a support group on Facebook for other journalists and editors who had gone through traumatic events. The group currently has almost 400 members.

“Here, you can give advice on how you coped from the secondhand grief, ask how to approach a source on a sensitive topic, and share tips on follow-up stories in the months and years ahead,” according to the page’s description.

Foster-Frau said many journalists are looking for answers on how to mobilize if and when their community experiences a mass shooting. “They want to find information about what the process is like, what resources are available, and what to expect professionally and emotionally.” The group has started a document, collecting tips, story ideas, links and words of encouragement for covering mass shootings.

For Miller, the Facebook group has been a “very gratifying project,” but seeing the number of members grow so quickly indicates there is a huge need for journalists seeking help.

As for the future of the group and its members, she said, “We just take it one day at a time.”

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here