In an era plagued by media consolidation, hedge fund ownership and gutted newsrooms — or “ghost papers” — investigative journalism has fallen by the wayside at too many newsrooms across the country. Investigative journalism is labor- and time-intensive and often expensive to produce. It also requires skilled journalists to do the work.

What does it take to create and lead an investigative team today? E&P asked five investigative editors that question.

Block Club Chicago

Mick Dumke is a 20-year veteran of investigative reporting in Chicago. He previously worked for the Chicago Reporter, the Chicago Reader, the Chicago Sun-Times and ProPublica. About a year ago, he took on a new challenge at Block Club Chicago.

“I spent most of my career writing about the city of Chicago and the ongoing tale of this strange and fascinating place, and I wanted to continue doing that,” he said.

The nonprofit neighborhood-level newsroom received a McCormick Foundation grant to start an investigative team. The mission was to investigate corruption and inequality, especially on Chicago’s south and west sides.

“There’s a saying among journalists in Chicago that every map we make, showing various indices or disparities, is the same map, whether it's lead poisoning, ticketing for bicycling on the sidewalks or gun shooting incidents. The red zones tend to be on the south and west side of Chicago, over and over again,” Dumke said.

Senior Editor of Investigations Curtis Lawrence joined the team a couple of months after Dumke, and they set out to hire three additional reporters.

The now five-member team is known as “The Watch,” and rather than be siloed, they work cooperatively with Block Club’s neighborhood reporters.

“The first project one of our reporters, Manny [Ramos], did was about the Chicago Transit Authority and some of its issues. That was done in conjunction with one of our beat reporters,” he said.

They sought journalists with investigative experience in Chicago or another similarly neighborhood-defined city to build the team.

“We wanted to assemble a diverse team, as well. It was essential to make sure that everyone was not just comfortable but had demonstrated skills and experience going out to parts of the city that, frankly, most of the public is not used to going to — or are scared to go to. We want people who can go anywhere and talk to anyone,” he said.

In addition to working with Block Club beat reporters, The Watch has had external partners, as well. Last fall, they worked with Illinois Answers to tell the story of how the local housing authority was sitting on hundreds of empty units at a time when people were desperate for affordable housing.

Dumke spoke about investigative reporting and potential trauma. One of Block Club’s neighborhood reporters witnessed a shooting last year. “We check in with each other as a team. It’s a policy at Block Club that mental health, safety and security are top concerns,” he said.

“We’re so privileged to do this work,” he continued. “It is hard, challenging and sometimes dangerous, but still such a privilege.”

Tampa Bay Times

Rebecca Woolington joined the Tampa Bay Times investigative team in 2018. She immediately began working on a project examining Tampa Bay's lead levels. She assumed the "anchor position" for the team, collecting data and reporting, and structuring the stories. In January 2022, former Tampa Bay Times Editor Mark Katches approached her about being the investigative editor.

Woolington described the investigative team today: “Bethany Barnes is the deputy investigative editor and senior reporter on the team. She is an incredibly dogged, extremely talented sourcing reporter. She can get anybody to talk to her, … and she’s a good listener.”

She described Investigative Reporter Zach Sampson as “incredibly precise and detail-oriented,” scientific-minded and a "phenomenal writer." So, too, is Hannah Critchfield, she said, adding that Critchfield is an exemplary sourcing journalist. Investigative Data Reporter Shreya Vuttaluru joined the team last June, and Woolington said she brings data and coding chops to the team.

They also work with other Tampa Bay Times reporters. For example, they collaborated with the Metro section to inform the public about the dangers of Kratom, an herb from Southeast Asia that’s responsible for an increasing number of overdoses in the region.

That particular investigation was surprisingly contentious. Pre-publication, the team received five letters from lawyers representing various parties in an attempt to intimidate them and challenge the veracity of the story. Those types of threats are pervasive in investigative reporting, Woolington said.

Asked how the team determines investigations to launch, Woolington said a story should reveal harm and wrongdoing. It should have scope and urgency.

“We don’t want vague accountability. We want to be able to name specific agencies, specific businesses and ideally, specific people responsible for wrongdoing,” she explained.

They’ve adopted a pitch process. Reporters must fill out a “pitch memo,” which includes a summary, what's new about the information and the potential scope.

“Scope is often proven through data, and a lot of times at the pitching stage, we might not have the datasets we want, so we define the datasets we’re going to go after,” she said.

The pitch memo describes who is harmed and whether there are explicit issues of inequity to address. It has a “supposed to” section that identifies laws or regulations these entities are supposed to follow but instead ignore or break them. A sources section lists potential documents, data and people to seek out.

Finally, reporters are asked about storytelling vision — for example, should it be a multi-part series? Should it be a narrative story, or is there potential to add graphics or multimedia? The pitch memo helps them decide if a story is worthy of chasing and provides a roadmap for their work.

CalMatters

In November 2023, Andrew Donohue was appointed investigative editor at CalMatters. Prior to the role, he’d been managing editor and executive editor of projects at the Center for Investigative Reporting. In 2005, he’d helped launch Voices San Diego, a local nonprofit newsroom.

“I was looking to get back into something that felt a little bit more local or community-based,” he said.

“And I wanted to join an organization with a strong identity and mission,” he added.

There were three reporters on the team already, and Donohue is in the process of hiring two more.

Throughout his career, Donohue has seen a change in how investigative reporters work. Once “lone-wolf operations,” today, the’re more collaborative. At CalMatters, they hope to build a team that includes reporters who speak Spanish and have data skills and expertise in public records.

Asked about resources and professional development opportunities, Donohue suggested Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE)/NICAR to other newsrooms trying to reinvigorate investigative journalism. Many of his own mentors and members of his professional network are relationships started at IRE conferences.

The dangers to investigative teams come from several sources, not the least of which are physical threats.

“Always keep in mind the safety of the reporters. Think about who the story is going to touch. Who might be unhappy? What kind of behavior have they been known for in the past? And how does the reporter feel? Are they physically safe? Do you need a plan if any threats arise,” he explained.

Their journalists also contend with social media harassment and doxxing. And then there are the legal considerations. A lawyer reviews every investigative story.

“But that doesn’t insulate you from the intimidation tactics used both pre-and post-publication,” he said. Being cognizant of those threats can help journalists take extra care in their reporting — in Donohue's words, “bullet-proof your stories.”

WBUR in Boston

Approximately five years ago, WBUR — the Boston University-based public radio station — enlisted veteran investigative reporter Christine Willmsen to create a new investigations team. Willmsen came to Boston after 16 years at the Seattle Times. It was an opportunity to stretch her storytelling legs in audio and to build a dream team of investigative reporters.

“I thought about what the talents you need in a team are, not necessarily in one person, but in a team collectively,” Willmsen said. She knew they needed expertise in data journalism and someone experienced in radio. She also wanted journalists adept at interviewing, sourcing and structuring stories for audio. And she knew they needed a “master at public records.”

“Massachusetts has one of the worst public records laws on the books. You just can’t get a lot of records,” she observed.

“Our first hire was Beth Healy from the Boston Globe, [now deputy managing editor], who had 20 years’ experience and had been on the Spotlight team,” she said.

Correspondent Todd Wallack became their public records guru. “He’s gotten judgments against several entities that have had to pay WBUR fines,” she noted.

One of the first investigative series they produced was about preventable deaths at local jails.

WBUR’s investigative team has also partnered with other newsrooms. “Our last story was a collaboration with ProPublica, which we co-published on MassLive.com and in a print paper, the Springfield Republican,” she said.

Impeding access to sources is a growing trend. Public officials refuse to go on the record or withhold their names. When dealing with private companies, public relations often intercedes, requiring questions in writing, allowing them to “polish, rewrite and sanitize” answers.

But the greatest challenges to their reporting come in the form of intimidation and menace by lawsuits. Two attorneys — Boston University’s lawyer and outside counsel — review all investigations. “That doesn’t prevent anybody from filing a lawsuit,” Willmsen said. “But I always want the reporters on my team, the day before airing or publication, to feel confident in the work and that the reporting stands up, so there’s rigorous fact-checking that goes on.”

In recent months, the team has reported on housing, the MBTA, the police department, domestic violence laws that shield abusers and more critical coverage.

“I like the idea that we were providing something to NPR listeners of our local station that they hadn’t heard before,” she said.

New York Amsterdam News

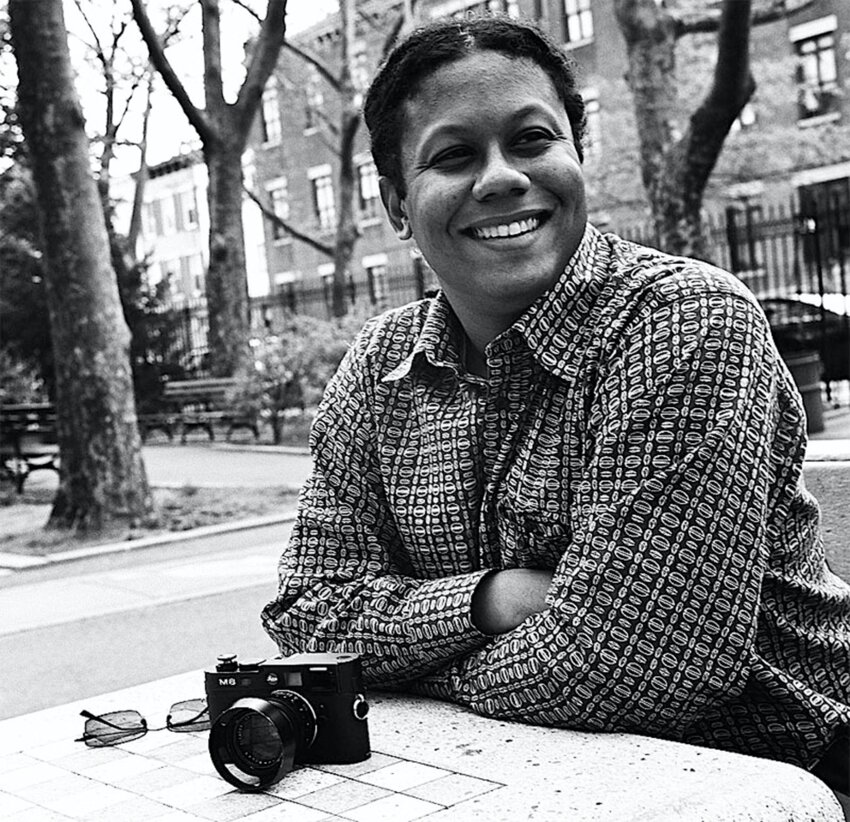

At the New York Amsterdam News, Damaso Reyes is the investigative editor who leads The Blacklight, a one-year-old investigative team.

“When we decided to build the team, the idea was to give ourselves the capacity to do this kind of long-form and enterprise work that was missing,” Reyes said. “Integrating that work into your day-to-day or week-to-week newsroom is hard. It really is specialty work, but it’s also that you need the time.”

Their first hire was Science Reporter Helina Selemon, who joined the team with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative funding.

“The challenge of grant funding is: how well does the funder's priorities align with yours? In our case, it wasn’t that we said to ourselves we needed a science reporter. It was, here’s a funding opportunity that aligns with what we want to do,” Reyes said.

“We’re interested in the impacts of climate change on communities of color, so in that sense, the science reporter would be great. … We launched a series looking at gun violence as a health crisis, which was another way a science reporter could work for us. And we’re continuing to do work around the impact of COVID on communities of color. We’d either launched or were planning to launch three projects that fit within that science bucket.”

They also hired Shannon Chaffers, a Report for America Corps member dedicated to the “Beyond the Barrel of the Gun” series.

Investigative skills can be taught and learned, Reyes said. It’s more important to hire journalists who can connect the dots, who come to the project with an open mind and challenge their own assumptions, he suggested.

In addition to IRE/NICAR, Reyes said investigative teams can tap into resources at the Poynter Institute and join associations like the National Association of Black Journalists.

The Blacklight team hasn't yet faced intimidation or lawsuits. “Truth is an absolute defense,” Reyes said. “I think the powerful, whether they be billionaires, corporations or special interests, need to be reminded of our role in our democracy. Sometimes, that’s an adversarial role. Listen, if we, as news organizations, do something wrong or malicious, we need to be held accountable. But we will not be intimated.”

“If we are self-censoring — saying we can’t investigate something because we might get sued even if we know the work is accurate — then why are we here? … We have to be thoughtful and diligent in our work, but if powerful interests bully and threaten us, that’s the ballgame.”

Investigative journalism isn’t merely a discipline for large, regional or national titles. Community news media is “closest to the ground” and thus capable of doing this kind of journalism, he suggested.

“This wasn’t just about doing this project for our newspaper,” Reyes said. “Obviously, that is the central part of it, but it was also to create a proof of concept for other small organizations.”

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here