By the time E&P’s November edition lands in readers’ hands, it’s entirely possible that the race for governor of Arizona will be decided and that the winner will be Kari Lake, the Republican candidate. Lake leaves behind a more than two-decade career in TV news to run as a Trump-aligned 2020-election-denying candidate for the state’s top executive position. On her way out, she cynically burned her professional bridges and made disparaging “the media” a cornerstone of her political platform.

Lake certainly isn’t the only former news pro to become a member of the political class they’ve been tasked with watchdogging. But her quick rise in politics raises questions about the current relationship between the press and politicians, the ethics of blurring those lines and what it signals to the public when a member of the press runs for office.

Professor Michael Schudson, Ph.D., of Columbia University reminded E&P in an email that this is far from a new phenomenon.

“Of course, 19th-century journalists often were political creatures overtly,” he explained. “Horace Greeley ran for president. Warren G. Harding was an Ohio newspaper publisher who became president. Joseph Pulitzer served a term or two in Congress. Hearst was a political operative who had presidential aspirations.”

Over the decades since, there have been dozens of cases of news people who turned to a life of politics.

Richard Warner Carlson — known as Dick and father to one Tucker Carlson — famously quit TV news to pursue his political aspirations. Malcolm Stevenson (Steve) Forbes Jr. straddled the world of news and politics, including two bids for the Republican presidential nomination.

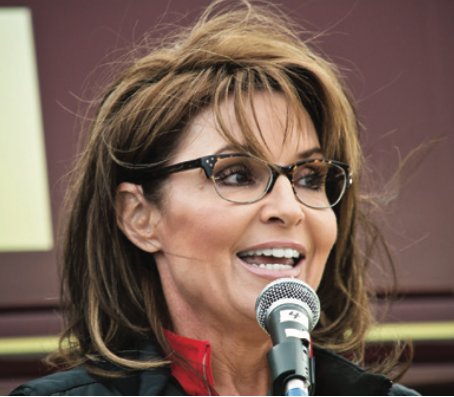

Sarah Palin remarkably went from TV sports reporter to Alaska’s governor to vice presidential candidate. This year, she campaigned for Alaska’s House seat but lost to her Democrat opponent in the special election. It wasn’t the only loss Palin suffered in 2022. In February, a jury tossed out her libel case against The New York Times.

While at the Detroit Free Press, M.L Elrick earned a Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting. In 2021, he mounted an unsuccessful bid for the city council there. Former investigative reporter Julie Akins became mayor of Ashland, Oregon. Diane Allen, a TV news anchor in Philadelphia, ran as a Republican to become a New Jersey State Senator for the 7th District, an office she held from 1998 to 2018.

Chris Hurst was an anchor on WDBJ in Roanoke, Virginia. After his girlfriend Alison Parker, a fellow on-air reporter, was horrifically murdered on live TV in 2015, Hurst left news, ran for office and was elected as a Democrat to Virginia’s House of Delegates in 2017.

Citing a desire to leverage his communication skills and conservative positions in Washington, D.C., former FOX4 TV anchor Mark Alford is the Republican candidate for the U.S. House seat representing Missouri’s 4th Congressional District.

The list goes on and on.

Freelance journalist and author of Columbia Journalism Review’s newsletter, “The Media Today,” Jon Allsop compiled a comprehensive list of broadcast reporters and anchors who subsequently tried their hand at politics. There are far more politicians who came out of broadcast than from print, and party affiliations appear split between Republicans and Democrats.

Nicholas Kristof had been a reporter and columnist for The New York Times for 37 years when he left his post to run (as a Democrat) for governor of Oregon. He’s a multiple Pulitzer nominee and a two-time winner. In 1990, he and his colleague and wife, Sheryl WuDunn, won a Pulitzer Prize for their reporting on Tiananmen Square and the pro-democracy movement in China. In 2006, Kristof won a second Pulitzer for his commentary on genocide in Darfur. He’s also authored several books.

Kristof’s candidacy ended when he failed to meet the state’s three-year residency requirement. Afterward, he reported that he was spending some time writing another book, a “journalistic memoir.” This past September, he returned to his former job as a Times columnist, covering issues of domestic and international importance, including homelessness, addiction and education.

Announcing his return, New York Times Opinion Editor Katie Kingsbury wrote, “In his ‘farewell’ column before running for governor of Oregon, Nick Kristof mentioned that when William Safire was asked if he would give up his Times column to be secretary of state, he replied, ‘Why take a step down?’ Now Nick is stepping up, resuming his Opinion column and once again interpreting the world’s depth and complexity for Times readers.”

Consider the ethics

The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) draws a hard ethical line regarding news professionals venturing into politics. In its position paper on political involvement, the opening paragraph reads, “The SPJ Ethics Committee gets a significant number of questions about whether journalists should engage in political activity. The simplest answer is ‘No.’ Don’t do it. Don’t get involved. Don’t contribute money, don’t work in a campaign, don’t lobby, and especially, don’t run for office yourself.”

Lee Banville is the director and professor of journalism at the University of Montana. He joined the faculty in 2009 after 13 years as the editor-in-chief of PBS’ Online NewsHour.

Banville said he doesn’t disagree with SPJ’s hard line but thinks it may be a “policy of a bygone era” because of some nuances, including the professional distinctions between reporters, columnists and TV news personalities.

“The job description of a columnist and the job description for a responsible political figure feels very similar,” Banville said. The greater ethical dilemma arises when political journalists dip their toes into politics, he suggested.

“Are you committing blasphemy if you’re a columnist one day and then you decide to enter the political arena, arguing the same stuff you’ve been arguing in your column? That feels different to me than if [you’re a] reporter. I feel like definitions are really important here,” Banville said.

Tim Gleason concurs. He’s the professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Oregon. Gleason remarked how successful on-air personalities have a skill set that translates well to politics, for which messaging, rhetoric and public speaking skills are paramount. He also feels there may be less controversy when a TV newsperson runs for office versus when a print journalist does it.

“I’m not suggesting that broadcast journalists are unethical or anything like that,” he said. “But I think with the culture of newsrooms at print papers, the barrier between political involvement and the profession is probably stronger. The line between news and entertainment is far less clearly drawn in many broadcast newsrooms.”

Gleason disclosed to E&P that he personally knows Nick Kristof and even fund-raised for his campaign. He spoke about Kristof and Lake as two examples from opposite sides of the political spectrum.

“I don’t pretend to know her politics,” he said, “but clearly, [Kari Lake had] been able to capitalize on her name recognition within the state. In fact, she’s quite clear that one of her advantages is that she is well-known based on her years as a broadcaster. … Nick is somebody who had done a lot of journalism about issues that he cared about and saw moving into the political realm as a way to address those issues in ways that he couldn't as a journalist.”

Gleason said that journalists often come to the news profession expressly because they care about issues of public interest, just as earnest politicians do.

He also suggested that The New York Times and Kristof smartly executed his transition as he stepped out of his columnist role and into state governance. “It was very transparent,” he said.

Still, he cautioned news publishers about the notion that journalists can just slip in and out of their roles as easily as Kristof made it look.

“I don’t think you could go through that revolving door too many times,” he said.

In a 2010 article, Slate’s former editor-at-large, Jack Shafer, considered what compels journalists to run for office. He wrote it at a time when his Slate colleague, Mickey Kraus, was mounting a campaign to represent California in the U.S. Senate. In the article, he opined about another TV news personality, J.D. Hayworth: “In Arizona, sportscaster-turned-member-of-Congress-turned-sports-anchor-turned-talk-show-host J.D. Hayworth has crossed over so many times, he can’t figure out which team he wants to play on.”

The synergies of journalism and politics

Since the advent of the printing press, the businesses of news and politics have clumsily intertwined. Media tycoons played at political kingmaking (and still do). Politicians bent the ears of reporters to see how their messages were playing to the masses.

“There is a lot of history of our columnists and writers who sort of ‘back channel’ with political leaders and sit down and help shape messages,” Banville said. “And sometimes they get involved in politics, but more like they’re advisors.”

And along the way, news people running for office further blurred the lines between the watchdog and the watched.

“It’s not a new trend, but I think it is a trend that maybe has been accelerated recently because of the divisive nature of our politics,” Banville said.

What draws journalists, editors or on-air news personalities to the political theater? The answer is likely nuanced and candidate-dependent.

“If you were to draw a Venn diagram of people who get involved in politics and people who get involved in journalism, there’s a lot of overlap,” Banville suggested, citing interests in civic engagement and institutional process.

Broadcast journalists have the added advantage of name and image recognition. A jump into politics is more a “short hop than a giant leap” for them, Banville said.

Arizona Governor candidate Kari Lake trades on that — crediting her career in news with her popularity while trashing the profession to arouse her base.

“It’s hard to think of a Republican candidate who hasn’t attacked the media in the cycle. … It would almost be weird if Kari Lake was not making the media part of her ‘liberal media establishment’ part of her talking points,” Banville observed.

When political polarization is at its worst, it often bodes well for the press — for example, “the Trump bump” during the 45th president's term. While the former president relished in disparaging the very media community he wooed for decades — portraying journalists as “the enemy of the people” — subscription and circulation figures climbed. But that’s toxic, Banville suggested.

“The economic model of journalism is playing to polarization right now. … But if half the country doesn’t believe us and actually believes that we are actively working to subvert democracy, that’s truly problematic,” he said.

From cozy to contentious

There is an element of public perception that sees the press as too cozy with politicians, and perhaps that’s compounded when members of the news media step out of their roles and into political ones. The University of Montana’s Professor Banville said that particular criticism was justified in the past, especially from the 1960s to the 1990s, but that “coziness” has given way to more of a "Cold War” between the press and political class.

Banville said the chill began with the Obama Administration, which “held the press at arm’s length” and became extreme during the Trump Administration. Today, stonewalling the press is de rigueur.

This semester, Banville is teaching a course on election coverage. Students are tasked to report on the midterms, and their work will appear in small dailies and weeklies across the state. One of the things Banville plans to stress with his students is the need for practical objectivity and the appearance of impartiality. For example, a critical tweet about Trump from years ago could be why a Republican candidate won't return their calls today.

“It allows a reader to dismiss everything you’ve written, and that serves nobody,” he said. “If you’re a good journalist, you’re a good journalist. And if you’re finding stuff out the public needs to know, we should get it to the public; we should try to get them to consume it, and don’t give them easy reasons to ignore you.”

While journalists turning to politics may not help restore the public’s trust in news, it may not be as destructive as other ethical breaches, according to Professor Gleason. “We still have rules that you can’t contribute to a political campaign because it would threaten the public perception of our objectivity,” he explained. “I think, as a general rule, that’s far too conservative and protective. But I do think that you shouldn’t have someone covering campaigns who has contributed to one of the candidates. It would be a very hard case to make that the individual doesn’t have bias. That’s far too cozy.”

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here