Accuracy is the core principle of quality journalism. When editors and journalists are dedicated to reporting the facts in a balanced manner, the public is more likely to trust what they write and publish — and become better informed and more involved citizens.

Traditionally, the job of most fact-checkers was to ensure information was accurate: people’s names were spelled correctly, statistics were cited clearly and statements by those interviewed were thoroughly vetted. The internet, however, added another dimension to fact-checking. The web became an easily accessed source of information and an open platform for individuals and groups to post misinformation, distorted facts and less-than-credible conspiracy theories.

The web’s fact-checking challenge and its use in political campaigns in the early years of the century impelled the Annenberg Public Policy Center to launch FactCheck.org in 2003 and the former St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times) to launch PolitiFact in 2007. PolitiFact is now a nonprofit project operated by the Poynter Institute.

Major news organizations, such as The Washington Post and The New York Times, quickly expanded their fact-checking staffs, especially as the political environment fractured, resulting in more misinformation.

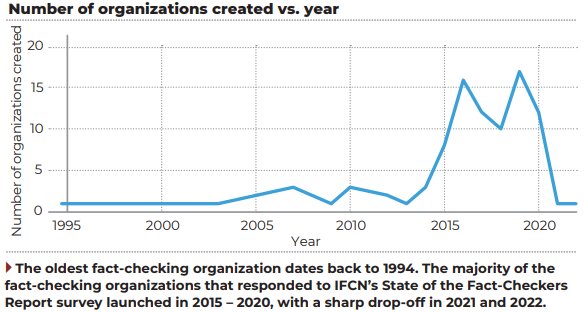

A September 2023 article from The New York Times reported a recent Monmouth University poll, which found 30% of Americans still think the 2022 presidential election was fraudulent, despite the efforts of fact-checkers at the Times, other publications and independent fact-checking organizations. The Times' reporters wrote, “The number of fact-checking operations at news organizations and elsewhere has stagnated, and perhaps even fallen, after a booming expansion in response to a rise in unsubstantiated claims about elections and the pandemic.”

During the writing of this article, fact-checking became even more challenging as major news outlets were suddenly flooded with misinformation prompted by the chaos in the U.S. House of Representatives and the horrendous events in Israel and the Gaza Strip. For example, in a mid-October Axios article, Wendy McMahon, CBS News CEO, said the network found only 10% of more than 1,000 videos of the Israel-Hamas war it analyzed were usable.

Specialized fact-checking organizations are proliferating, too, such as Science Feedback, founded in 2015 in France. As climate change became a fertile ground for scientific misinformation and misinterpretations, it added the Climate Feedback blog to “verify the credibility of claims related to climate change, the environment and Earth sciences.” The Health Feedback blog aims to counter unsound statements about the pandemic and new vaccines.

Exposing misinformation on a global scale

Another Poynter fact-checking program, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), was launched in 2015 to address the same online misinformation problem fact-checkers and media outlets were experiencing worldwide. Fact-checking organizations and media groups can become verified signatories to the IFCN’s Code of Principles and then access IFCN grant opportunities, training, events and the global fact-checking community.

Angie Drobnic Holan is the director of IFCN, which received a record-breaking 61 new applications in 2023. As a result, it paused accepting new applications until January 2024.

“We’re receiving many applications from groups in smaller countries where there is an increasing awareness that the misinformation on the web is a societal problem that fact-checkers and journalists must address in the countries where it’s happening,” Holan said.

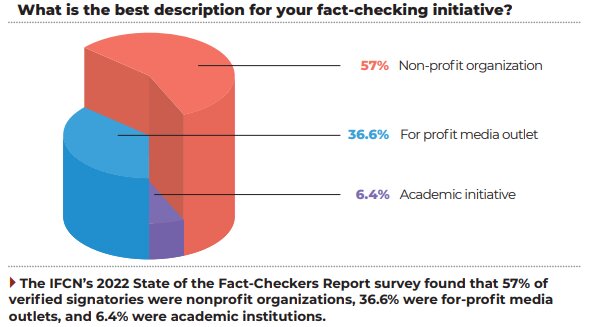

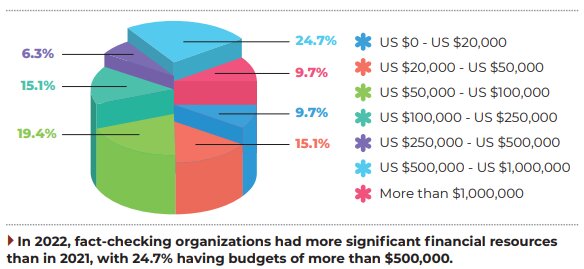

The IFCN’s 2022 State of the Fact-Checkers Report survey found that 57% of verified signatories were nonprofit organizations, 36.6% were for-profit media outlets, and 6.4% were academic institutions. More of these signatories had more significant financial resources than in 2021, with 24.7% having budgets of more than $500,000.

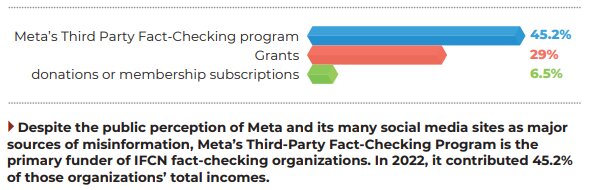

Despite the public perception of Meta and its many social media sites as major sources of misinformation, Meta’s Third-Party Fact-Checking Program is the primary funder of IFCN fact-checking organizations. In 2022, it contributed 45.2% of those organizations' total incomes.

“Following the first international conference in 2014, fact-checkers wrote an open letter to Meta suggesting it work with fact-checkers because of the significant amount of misinformation they found on its social media sites. Meta launched its program at the end of 2016,” Holan said.

Holan added the program promotes a two-way conversation between fact-checkers and Meta, and fact-checkers are not hesitant to tell Meta when improvements and changes are needed.

“I think Meta deserves some credit for supporting fact-checkers’ work online. Not all of the tech platforms do. TikTok does. On the other hand, YouTube does not have a similar program, although Google and YouTube have also provided grants to fact-checking organizations,” Holan said.

Fact-checking in Wisconsin’s highly competitive political environment

Wisconsin is a pivotal swing state for many presidential elections, even more so during recent election cycles. According to Greg Borowski, executive editor of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the state is often a focal point of all sides of a campaign or an issue, resulting in many ads and flyers and social media attention from candidates, PACs and other organizations.

“Fact-checkers are calling balls and strikes. Some might argue that’s not the role of a journalist and is inherently biased. I disagree. Our job is to have a consistent strike zone and to let everyone — readers and politicians alike — know what it is. Then readers can use our information and rating to draw conclusions,” Borowski said.

The Journal Sentinel has been a PolitiFact partner since 2010 and was one of the first state-level PolitiFact sites. During his more than 30-year career, Borowski has witnessed the rise of the fact-checking movement and how that work has changed.

“The main thing that has changed is how misinformation can be targeted and delivered. Tactics are much more sophisticated, as are the tools that can deliver the message directly to specific groups via geolocation, emails, text messages, Facebook ads, etc. It’s harder to address and even — often — harder to know what message is being sent, where and by whom,” Borowski said.

When asked for his advice to journalism students who may want to become fact-checkers, Borowski said reporting experience isn't necessary but will give students a good foundation. Understanding the mechanics of government will add to their fact-checking skills.

“As important as the hunger to get to the bottom of a claim, a deft prosecutorial mindset to examine fully any claim and clear thinking to explain your conclusions to readers in a direct, straightforward way are the skills of a good fact-checker,” Borowski said.

Bob Sillick has held many senior positions and served a myriad of clients during his 47 years in marketing and advertising. He has been a freelance/contract content researcher, writer, editor and manager since 2010. He can be reached at bobsillick@gmail.com.

Bob Sillick has held many senior positions and served a myriad of clients during his 47 years in marketing and advertising. He has been a freelance/contract content researcher, writer, editor and manager since 2010. He can be reached at bobsillick@gmail.com.

1 comment on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here

formereditor

Journalists have forgotten their mission - to report news without bias. Judging from walk-backs or corrections of leading media outlets, certainly during the Trump years, along with those awarded Pulitzer Prizes for reporting falsehoods, one would think journalism leadership would press the big red reset button. The dis-mis-mal-information brouhaha is nothing more than an attempt at gaining partisan control. Totally unnecessary, if tenets of journalism are followed: 1) write an honest headline - no clever clickbait 2) Use credible, named sources . . . 3) . . . from opposing viewpoints, with a balanced approach from both (a reporter is outside the story, looking in) 4) Absolutely no leading questions to fit a narrative - only to develop a balanced story 5) leave personal opinions out of the story, unless it is clearly identified as an opinion piece. Understand that "truth," like "science," is fallible, based on human perception at a point in time and space. This is why law enforcement relies so heavily upon "motive." It's time real journalists went on the offensive, shedding their partisan skins for the higher calling they chose to indulge for the good of society.

Wednesday, November 29, 2023 Report this