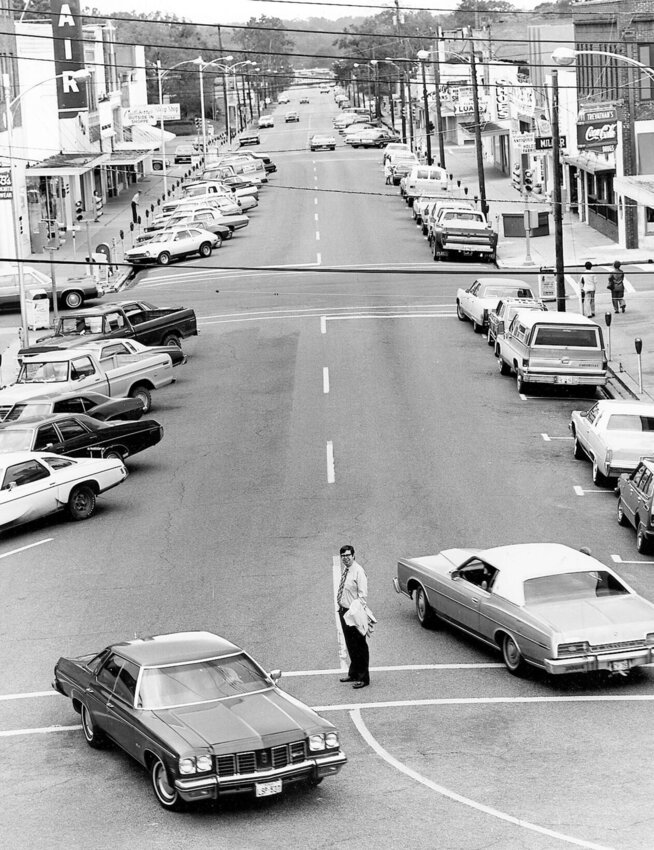

In a storied career that would eventually lead him to travel the globe, Joe Murray was awarded journalism’s highest honor — and earned The Lufkin Daily News national acclaim — for a series of stories reported without ever setting foot outside his hometown.

The iconic journalist died at his home Sunday, June 25, at the age of 82. Services will be at 2 p.m. July 5 at First Baptist Church.

While editor of the paper, he and then-cub reporter Ken Herman won the Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service in 1977 for a series of articles leading to reforms in military training and recruiting practices.

But the lofty accomplishments and far-flung travels never changed who Murray was at his core: a folksy, down-to-earth guy readers could easily relate to and a true character friends and colleagues genuinely enjoyed.

“He once told me he only wanted to be remembered as a ‘country journalist,’ but his impact stretched worldwide,” said Phil Latham, who worked with Murray at The Lufkin Daily News.

And while he was “a first-rate journalist,” LDN colleague Heber Taylor said Murray lived a full life outside the newspaper.

“He was well read,” Taylor said. “He had more literature in his head than some colleges have in their libraries. He seemed to have read everything before the reviews came out.”

Murray loved Paris, was good to those who worked for him and spoke often of his family, Taylor said.

“It was a big family, including children, cousins, distant kinfolks and dogs,” he said. “The people he loved and cared about came in different colors and with different creeds. He talked eloquently about his wife. He said that was the great mystery of his life: the love he shared with Sarah.”

Latham calls Murray “the most passionate journalist I have ever known.”

“He believed in the public’s right to know and was, at a moment’s notice, ready to do fight for that right,” he said. “Unlike authors, journalists are rarely remembered long after they are gone but what Joe accomplished remains. This is a sad day for Lufkin.”

Herman describes Murray — who not only guided him as a young journalist straight out of college but also introduced him to the woman he would marry — as someone who was “improbably very important to my life on so many counts, personally and professionally.”

“He just was a great newspaper man, and there just aren't many people who are that good at what they do who will decide to spend their lives in their somewhat small hometown and not feel the lure of moving up to bigger cities, bigger newspapers. But Joe made Lufkin, his hometown, a better city with what he did for journalism.”

Herman, who was “a kid out of college” when Murray offered him the job at The Lufkin Daily News, said his mentor’s influence extended beyond “only the professional stuff.”

“He was just important in the little, very subtly offered lessons about life and the proper way to do things,” Herman said. “He will be missed.”

Murray, whose father had worked at The Lufkin Daily News as a Linotype operator, worked various jobs at the paper as a high school student and during summer vacation while he attended the University of North Texas at Denton, fellow journalist Jay Milner wrote in his 1998 memoir “Confessions of a Maddog: A Romp Through the High-Flying Texas Music and Literary Era of the Fifties to the Seventies.”

He then worked for a couple years as the East Texas correspondent for the Houston Chronicle in the mid-1960s before returning to the newspaper. In June of 1969, then-Lufkin News publisher Tom Meredith tapped Murray as editor, making him the first Lufkin native to head up the newsroom.

It was in 1977 that the careers of Murray and Herman became forever intertwined when they received journalism's highest honor: the Pulitzer Prize.

“Ironically, the series won only a second place award in statewide competition among Associated Press newspapers earlier that year,” as historian and journalist Bob Bowman noted in a 2007 article commemorating the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.

The stories documented the recruitment and death of Lynn “Bubba” McClure, a 20-year-old Lufkin resident who died during a training exercise at Marine Corps boot camp in 1976.

McClure died after participating in a series of pugil-stick bouts at Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego. Participants recalled that McClure, by way of trying to toughen him up, had been required to fight a series of bouts against larger, stouter opponents. A blow to the head proved fatal.

In an LDN article highlighting the 40th anniversary of the Pulitzer win, Herman said he had no idea at the time that the story would make such a huge impact on military recruiting tactics.

“We got a letter inviting us to enter the Pulitzers,” Herman said. “We were so excited by that letter that I believe Joe had the letter framed and hung up in the newsroom. We figured that was good enough. There was zero expectation (that the stories would win).”

In a 1977 New York Times article about Murray and Brooklyn native Herman’s win, Murray’s modesty and sense of humor were on full display.

“I keep thinking somebody is going to call back any moment to say that it was not the Pulitzer Prize that we won, but something called the Pleurisy Prize for our stories on the city‐county health unit,” he told The Times.

The stories focused on irregularities in tactics used by some Marine recruiters and the Corps training programs as well as special “motivation” platoons for difficult recruits.

The article showed McClure was not mentally qualified to join the Marine Corps and had volunteered to enter a state hospital. The stories also revealed that recruiters failed to check with police officers in Lufkin, and McClure had been coached so he could pass his second Marine exam.

With help from then-U.S. Rep. Charlie Wilson, the stories led to congressional hearings and reforms in Marine Corps recruiting and training. The Marine Corps reprimanded some of the officers involved and court-martialed non-commissioned officers.

As a result of The Lufkin Daily News’ reporting, other Texas newspapers also published stories of Marine recruiting tactics and training.

“There wouldn’t be a Pulitzer in Lufkin had it not been for publisher Tom Meredith,” Murray said in that 2017 article. “When Ken and I laid out the story to him, he said, ‘Go with it,’ and never so much as blinked. For a newspaper editor, that amount of trust is worth all the gold in all the gold medals. Over the years, our little paper had any number of controversial stories, but I never felt I was up against the wall. Tom Meredith had my back. He was always between me and the wall.”

The gold medal is on display in the lobby of The Lufkin Daily News office, along with the letter notifying Murray of the win.

“A small newspaper with limited resources chose not to settle for the official explanation," the Pulitzer Prize committee said.

Murray, who had served the LDN as editor and publisher since 1978, was named special writer for Cox Newspapers in 1989 and began traveling the world, filing columns that ran in newspapers across the country. And when he wasn’t on the road, he stayed home and wrote about his neighbors, continuing his column until his retirement in 2000.

“Joe has this knack, this talent, for finding the town's, or city's or village's most interesting characters and getting them to talk freely about themselves, their lives, their countries, political conflicts and anything and everything else that interests them,” Milner wrote in his book. “‘How do you do that?’ I once asked. ‘It's what I do,’ he answered. Among the things Joe and I found we had in common was a love of good stories, telling them and hearing them. Joe said there are two kinds of people: joke tellers and storytellers. We laughed at a good joke, but we preferred a good story every time.”

Herman said Murray “was just a good guy.”

“He was very funny, and he could laugh at himself, which too many people can't do,” Herman said. “And he could laugh at sometimes the foibles of his small town, and in any small town — especially if you're as ingrained in it as Joe was — there are characters and situations you’ve got to laugh at. And he understood that.”