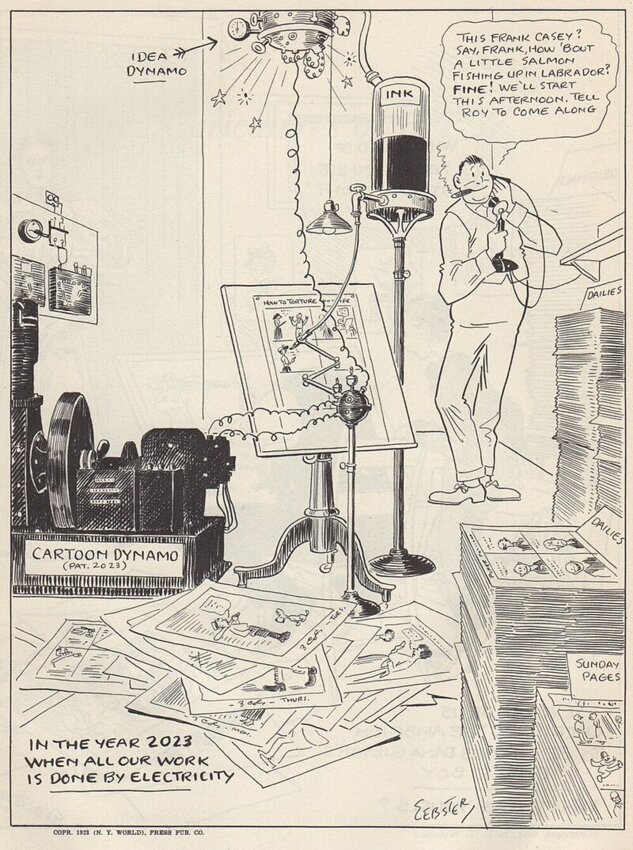

More than a century ago, cartoonist H.T. Webster imagined a newsroom of the future where computers were capable of creating content.

In a cartoon that appeared in a 1923 issue of the now-defunct New York World, Webster showed a cartoonist on the phone making fishing plans while the “cartoon dynamo” knocked out his work that day. “In the year 2023, when all our work is done by electricity,” Webster noted in a caption.

Sound familiar?

Today, digital tools powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI) can create artwork, string together paragraphs of readable text and produce realistic video and audio easily confused with something made by a human being. But it’s important for journalists to remember there’s no real intelligence in artificial intelligence — at least not yet.

Emily Bender, a computational linguist at the University of Washington, prefers the term “stochastic parrots” because these AI-powered tools mimic words without an ounce of understanding. In his AI Snake Oil newsletter, Princeton professor Arvind Narayanan (along with doctoral student Sayash Kapoor) was a bit more direct, calling generative AI-powered chatbot ChatGPT “the greatest bullshitter ever.”

“These language tools can make it seem like they know everything, and in fact, they literally know nothing,” said Will Oremus, who covers AI and technology for The Washington Post. “They can give a plausible response to just about any prompt, but most of the time, it won't be grounded in reality. And that can be really dangerous.”

The pace at which generative AI is overtaking the tech world is causing a wave of anxiety to ripple through the world of journalism. After all, most news organizations are still grappling with technology-powered changes that upended the profitable newspaper bundle over two decades ago. Now, some of the same tech giants that once pledged to help news organizations transition to the digital world are behind this new technology promising to make life easier for journalists.

Larger news organizations are already beginning to react. The New York Times is building a team of engineers and editors to explore and experiment using generative AI tools in the newsroom. The Washington Post named Phoebe Connelly as its first-ever senior editor for AI strategy and innovation back in February, while The Wall Street Journal is in the process of hiring a newsroom director of AI “to shape and direct our response to this exciting and fast-developing area.”

That’s fine for news organizations with the resources and staffing to throw at these new technological advances. But it leaves smaller newsrooms, especially those not owned by a national chain, left attempting to navigate an overwhelming flood of information about the rise of AI systems and how they might be beneficial.

What is the advice from Oremus and other tech experts? Proceed with caution.

For starters, these Large Language Models (LLMs) are trained on content scraped from across the entire internet. The more content surrounding a subject, the more likely AI-powered chatbots will come close to pumping out accurate text. For example, if you ask questions about Barack Obama, it's more likely to deliver a factual response than if you ask about a local politician.

“If you ask a question about a local councilperson without a ton of data to draw on, it might just make something up that sounds as true as possible,” Oremus said. “And then if you ask it to cite its source, it may even make up the most plausible-sounding citation, but that citation won’t exist, more often than not.”

These happen so often with AI chatbots that they have an official term — hallucinations.

In his Technology 202 newsletter for The Washington Post, Oremus offered the recent example of tech entrepreneur Vivek Wadhwa. A former Washington Post opinion contributor, Wadhwa was using WhatsApp’s new AI chatbot when he was presented with a 2014 blog post accusing him of plagiarism, complete with a byline and citation. It turns out the blog post never existed, and neither did the citation. The chatbot made it up.

Another thing to remember about the potential pairing of these new AI tools and journalism is that we often report new stuff, which means LLMs haven't been trained to handle it. Despite the lingering issues, we’ve seen what happens when news organizations rush to use these new tools.

Last year, Gannett paused a generative AI experiment after publishing widely mocked computer-generated stories on high school sports robotically repeating clunky phrases like “a close encounter of the athletic kind.” CNET paused its efforts after finding errors, including potential plagiarism, in more than half its AI-written stories, the Verge reported.

That doesn’t mean it’s all bad news for journalism.

Reporters at The Washington Post use Amazon Textract — which extracts text and data from scanned documents — when digitizing files for investigative work. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a German newspaper, uses Google’s AI services to help editors predict which stories should go behind their paywall.

The New York Times does something similar with its machine learning model, the Dynamic Meter, which helps set personalized paywall meter limits. Aftenposten, the largest daily newspaper in Norway, uses a custom AI-generated voice to provide audio for its stories. The voice is trained on the actual voice of its podcast host, Anne Lindholm.

Felix M. Simon, a doctoral candidate at Oxford, outlined several surprising ways newsrooms already utilize AI-powered tools in a study called “Artificial Intelligence in the News” for the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. One example Simon outlined in a conversation with Politico’s Jack Shafer was at The Daily Maverick in South Africa, which uses AI systems to create bullet point summaries of their long-form content.

One way journalists could get their feet wet using generative AI tools is as a brainstorming device. Despite their flaws, Oremus says these AI-powered chatbots are great at rearranging words, so they excel at tasks like summarizing articles into bullet points or checking for proper grammar and spelling. One thing Oremus sometimes does when writing stories is ask a chatbot about the subject he’s covering — sometimes, the prompt helps him brainstorm angles he hadn’t considered or aspects he may have overlooked.

Another great time to use a chatbot is when you're trying to remember a specific word, but it doesn’t have an exact synonym to look up in a Thesaurus. For instance, when I asked ChatGPT, “What is the word that begins with the letter ‘c’ that describes the captions displayed during newscasts?” it helpfully shot back, “Chyron.”

In that light, it’s easy to see some of these tools deployed within newsrooms to help provide copy editing and guide copy toward their newsroom's stylebook. One of my favorite AI-powered tools is Headline Hero, a web-based program developed by the team at Newsifier that helps brainstorm headline ideas based on what you’ve written. Another favorite is Lose the Very, an appropriately named tool that helps rid your copy of all those needless verys.

“I think there will probably be many ways these AI tools can be useful on the margins for journalists,” Oremus said. “But the downsides of relying on them to write anything factual are huge.”

Rob Tornoe is a cartoonist and columnist for Editor and Publisher, where he writes about trends in digital media. He is also a digital editor and writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Reach him at robtornoe@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here