On any given day, the American people can find coverage of the U.S. border with Mexico — in print, online and circulating on social media, TV and talk radio. Partisan media outlets and politicians alike often sensationalize the coverage. But to truly understand what’s unfolding there, as well as the challenges journalists face in reporting on the border, E&P went to the sources.

Reporting on a lived experience

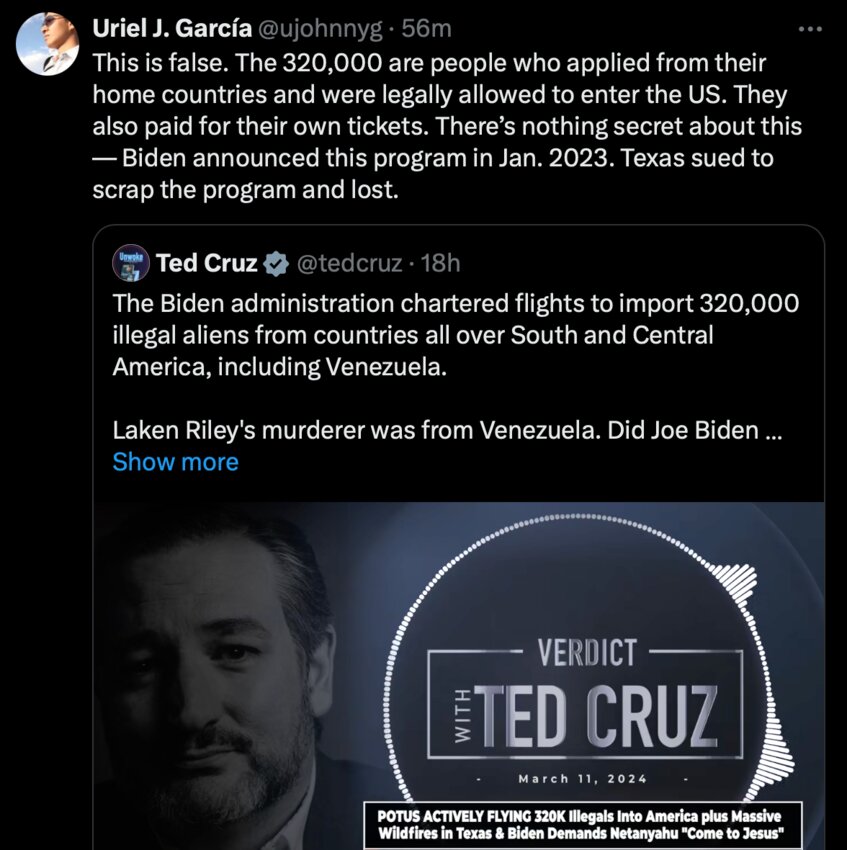

Uriel J. Garcia is an El Paso, Texas-based immigration reporter with The Texas Tribune.

“What I have appreciated the most is that the Tribune management respected not just my reporting techniques but the fact that my life experience complements the work I do,” he said.

Garcia came to the U.S. when he was a year old. His family crossed the Sonoran Desert, and he grew up as an undocumented immigrant in Phoenix. Garcia aspired to college and chose journalism as his career. During his college years, he became keenly aware of how the media covered immigrants in stereotypical ways. As he became a citizen, he watched as laws were passed to make it more difficult not only to immigrate to the U.S. but to live wholly and safely once settled here.

Even today, Garcia is troubled by the language often used to describe people crossing the border, especially the term “illegal.” Not only is it not illegal to seek asylum, using the term doesn’t consider due process, he said. A person accused of murder is not called a murderer. They are innocent until proven guilty.

“Why is it that when we write about certain populations, we’re more careful, but when we write about immigrants, we can just call them illegal,” he said.

Garcia travels to points along the border, including Eagle Pass, McAllen and towns in the Rio Grande Valley. Sometimes, he makes the trip with a particular mission in mind. Other times, he takes several days to talk to people — residents, city councilors, county judges, advocacy groups and migrants.

“I think people don’t realize that people in these towns get up and go to jobs and schools, regardless of the so-called wave of migrants coming in. The cities still move. The towns are still operating. Nothing is shut down, except sometimes bridges. Day-to-day, things continue,” he said.

Residents are usually happy to talk. “With immigrants, it’s a little different because sometimes they are fleeing people who are trying to harm them. They worry about who I am. Where is this story going? What am I going to do with their photos? What am I going to do with their name? And a lot of times, they share very traumatic and intimate details that may be easily identifiable,” Garcia said.

He noted that while the politicization of the border is prevalent in the states, most people who come to the border are unaware they may not be welcome.

Garcia cited harsh immigration laws passed as far back as the Clinton Administration. “It has made it easier to deport immigrants, regardless of their status, like Green Card holders. … As journalists, I don’t think we've done a good job explaining why it is so hard to come to the U.S. legally and be able to stay permanently,” he added.

Reporting on the border, especially the underlying violence, can be traumatic and cause you to feel helpless, Garcia said. He spoke candidly about questioning whether his work matters when it seems nothing changes.

“I’ve come to realize, if we’re not doing this, who else will,” he said.

Beyond the border

Monica Eng reports for Axios Chicago. She’s been following the stories of people who crossed the border and were bussed to Chicago — their difficulties getting work and the broader impact their arrivals have had on city services and residents.

“[Chicago] Mayor Brandon Johnson came into office last year with a lot of big ideas, but people have said this is his COVID. … It consumes every city council and every press conference. There's always something about it at every meeting. And it was orchestrated to bring border issues to Chicago, and it has succeeded, probably beyond Greg Abbott’s wildest dreams,” she said.

When asked how these stories resonate with readers, Eng said the responses are mixed. Some want to help, volunteer or donate clothing and food. Others question why services aren’t being spent to help long-time Chicago residents in need.

“It’s an issue that has really divided the city, and that shows up in letters from readers,” she said.

For journalists, describing immigrant populations can be fraught. Eng explained, “A lot of people use ‘asylum seekers’ as a blanket term, but I dug in to see how many are actually formally seeking asylum, and it’s actually a very small number. We don’t go with that blanket term. I’ll say migrants or people or new arrivals, or specifically say Venezuelans, because that’s the largest portion of our new arrivals.”

Getting information from agencies, such as work permit statistics, can be difficult, but another challenge is access to immigrants. “Some agencies don’t want you to talk to them because if they end up seeking asylum, but they’ve told a journalist — with their name attached to it — that they wanted a better life for their kids or that the economy is bad in Venezuela, that can really hurt their case.”

Eng is herself from a family of immigrants. Her grandmothers came from China and Puerto Rico, and her grandfather from Peru. She knows how difficult the path to citizenship can be. Asked why there isn’t more path-to-citizenship news, she said, “Because there really isn’t a great path to citizenship for these particular groups that have been entering the country over the last two years.”

Reporting on law enforcement

Following his work for Talking Point Memo, Matt Shuham joined HuffPost in 2021. He reports on a wide range of topics, including immigration. In February 2024, he wrote about “Operation Lone Star,” Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s border initiative. For the story, he spoke with law enforcement there.

“I found them quite willing to talk about their experiences, and they’re not hard to find,” he said, citing online forums like Reddit.

“They’re eager to tell me what they think is going right and what they think is going wrong. They’re also eager to tell me that public perception is off. Some tell me to f-off or talk to public affairs, which is non-responsive or non-existent, but many of them tell me they think the public has a right to know what they’re doing with their tax dollars.”

Shuham’s work shed light on the challenges soldiers face at the border — violence, lack of housing, alcoholism and suicide among them. A segment remains confident in the mission, while a great many refer to Operation Lone Star as a “political stunt” and “not effective immigration enforcement.”

Shuham discussed with the soldiers how difficult it is to appeal for asylum at the border: “Imagine getting to the border, trying to download an app to schedule a time to surrender to border patrol at a port of entry, only to find the app is broken. Meanwhile, they face the threat of kidnapping, rape and murder in Mexico. What would you do in that situation? You’d find a low-lying place in the Rio Grande, cross, and be charged in Texas with trespassing or misdemeanor illegal entry. Then you’d apply for asylum, and the end result is that you’re vilified as an evil person. That just blows my mind.”

Traveling the border

Sandra Sanchez is an award-winning journalist with a three-decade career as a reporter and opinion editor. She joined BorderReport.com when it launched in 2019, and immediately embarked on a two-week border tour, traveling from San Diego to the Rio Grande Valley. Their coverage earned a National Edward R. Murrow Award.

“You have to be on the border to report on the border,” Sanchez said. In addition to writing for BorderReport, Sanchez also produces spots for Nexstar-owned TV stations, locally and across the country and is a talk-back guest on other networks, like CNN.

The week before she spoke with E&P, Sanchez was with President Biden on his first trip to the South Texas border. Though the President walked the border and spoke with law enforcement there, he followed it with a prepared speech that didn’t address what he actually observed and learned. It was a missed opportunity, according to Sanchez, to tell the American people about things like the thousands of drones the cartels use to evade border agents, how the U.S. needs surveillance technologies, and how complicated enforcement is.

Sanchez feels frustrated when journalists get basic facts wrong — for example, incorrectly identifying Customs and Border Protection agents versus U.S. Border Patrol agents. At any time and place, other law enforcement agencies could be operating there, including local sheriff departments, the National Guard, Texas State Troopers, and “AMO” (Air and Marine Operations). Advocacy and humanitarian groups also need to be correctly identified and interviewed. Many of these agencies refuse or limit journalists’ access to sources.

As an experienced border reporter, Sanchez knows about laws and protocols, such as a Texas law prohibiting anyone — even the press — from being within 150 feet of the border wall. Press credentials are necessary at all times, and journalists are always under surveillance. Every moment presents a dilemma. She recalled a chance encounter with a border patrol mobile scope truck — mobile-mounted cameras with infrared and night-vision cameras that can see for miles.

“The technology is very expensive, and you never know where it will be on the border,” she explained. She wanted to film it but had to vow not to show agents’ faces, the license place, or any identifying landmarks that would tip off smugglers to its location.

“You have to understand that you could possibly harm an agent. They could be overwhelmed by the cartel, but at the same time, you’re trying to get information to explain it,” Sanchez said.

The border beat is often perilous and traumatizing. Sanchez recounted the lingering memory of a trip to Eagle Pass when she observed families navigating sharp buoys and concertina wire. They were throwing small children over the razor wire to someone on the other side. A young boy sobbed as his mother tried to climb over, only to be caught, her skin repeatedly impaled and bleeding. He ran barefoot across the burning sand on a 112-degree day to Sanchez, begging her for water. She gave him all the water she had — a staple in her gear — and watched as the family choked it down and settled under a tree, anticipating their arrest by border patrol. The little boy returned to her, crossing the hot beach again, his feet blistering. “And he told me in Spanish, ‘Thank you for the water. God bless you. May you be blessed.’ I got in the car and gave myself 30 seconds just to melt down and cry. Like, he thanked me, yet I did nothing. I did nothing. I filmed his mother bleeding.”

For safety, BorderReport doesn’t allow its journalists to cross into Mexico, which Sanchez said is a little like doing her job with one hand tied behind her back. She takes breaks when she can, managing her mental health with exercise, yoga and long walks with her dogs. There are stories not being told about the border that she’d like to see other news outlets run with — stories of how migrants are economically benefitting their towns.

There’s a lot of myth-busting to do, too. She cited a federal proposal to hire 100 more immigration judges and more asylum officers to address a 3.2 million-case backlog. There’s a desire for 10,000 more detention beds.

“These are just numbers they throw out, and people eat them up. But if you stop and think about 10,000 people coming across in Arizona towns or Eagle Pass, Texas, on any given day, that’s not going to do anything. Dig into the numbers,” she pleaded.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here