The term “objectivity” is itself subjective. If you were to poll the public about their desire and demand for “objective” journalism, many might opine that reporters should stick to the “who, what, when, where and why” model — sans the “why” part. But the “why” is, after all, the essential context of the story, and without it, the public is less informed and not as inclined to read the bare-bones carcass of the story that remains. Of course, contemporary conversations about objectivity and fairness in reporting are much more nuanced and complex.

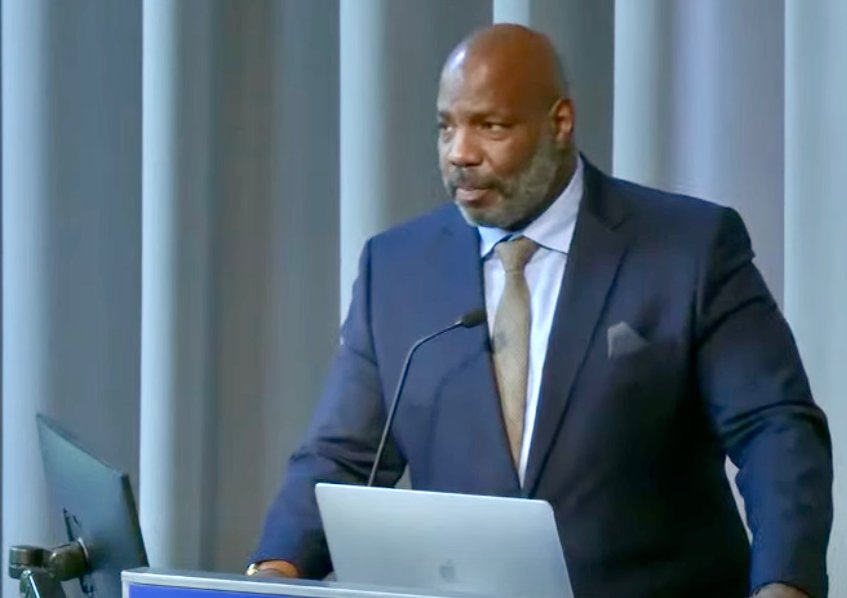

The Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) and Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights at Columbia University hosted a symposium in mid-September on the topic of objectivity. The recently appointed dean, Jelani Cobb, Ph.D., opened “The Objectivity Wars," a panel discussion moderated by CJR's editor and publisher, Kyle Pope. Pope was joined by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Wesley Lowery; David Greenberg, professor of history, journalism and media studies at Rutgers University; Masha Gessen, staff writer at The New Yorker; Lewis Raven Wallace, author of “The View from Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity” and former “Marketplace” host on public radio; and Andie Tucher, the H. Gordon Garbedian Professor of Journalism at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism.

The concept of objective journalism is a relatively new phenomenon, Professor David Greenberg suggested. “For much of the 19th century, you had an overtly partisan press, much like Fox and MSNBC, which made no secret of which party or side they are aligned within their general kind of news presentation.

“They had names like the Springfield Republican or the St. Louis Democrat. You could tell where their politics were,” Greenberg continued. “In the late 19th century, you began to see sort of an emergence of professionalism in a lot of fields, like law and medicine — in the social sciences, in particular — and the emergence of positivism, of a kind of factually-oriented approach to gathering and then distilling and analyzing information, which kind of made its way into journalism, as well.”

In the 1960s, things changed. Outlets like The New York Times, Reuters and The Associated Press became “places we go to get the news uninflected,” he suggested.

But Greenberg sees room in the media spectrum for both approaches to news. “I think the strength of the American system over the last 100 years has come from the fact that we’ve actually had both of those models in play,” he said.

One of the pitfalls of objective journalism as a singular goal is the trap of “both sides-isms,” when reporters present two perspectives on a story, even when one side of the story is closer to the truth and the other is speculative, conjecture or just plain false.

“But there’s another pitfall, of course, which is going in the opposite direction and veering into editorializing bias. I mean, objectivity, in a way, is the attempt to identify our own biases and correct for them,” he said.

Andie Tucher, who authored the book, “Not Exactly Lying: Fake News and Fake Journalism in American History,” expounded on the historical evolution of objective journalism, referring to 19th-century journalism as “terrible” and “embarrassing.”

“Journalism was not just politically partisan; it was also invented,” Tucher said. “Interviews were routinely invented, and they talked literally about how much fun it was to fake. You could see it in the trade journals.”

In response to the “fake news” of the day, more reputable outlets adopted the objective approach, with fact-oriented evidence-based reporting, Tucher explained to the audience. Today, “fake news” outlets take great pains to appear as if they’re objective.

“If you look at the web pages of Breitbart, Project Veritas, InfoWars or Sinclair Broadcasting, any of those Fox news, deeply partisan, often crazy conspiratorial news organizations are the ones who say, ‘We are doing objective work. We’re doing accurate work. We are impartial. Truth is our banner.’ If you look at that and compare it to the responsible and careful news organizations that are really trying to work their way through how to deal with this strange and difficult value of objectivity. They’re not talking like that. They’re talking about transparency,” Tucher noted.

Pope asked Lewis Raven Wallace about the author’s Medium piece, “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it.” Wallace was fired from a job in public radio for publishing the blog post. Wallace recounted coming out as queer and trans as a teen and coming at the profession of journalism with an activist perspective.

“For me, it was about telling the stories of my life and my existence, the people I was in the community with — young people, queer and trans people, people of color — who weren’t being represented in mainstream news outlets, or were being misrepresented,” Wallace explained, adding that it seemed as though objectivity became a tool to silence those voices. But Wallace recalled “following the rules” for five years.

“And then, when Donald Trump was elected, there was this increased anxiety about this question in newsrooms. I was working in a national newsroom covering the economy, and their real day-to-questions were like, ‘Okay, if we’re going to run two stories today about something that Trump lied about, do we need to do a third story about something that he did, you know, that was good?’ That kind of stuff. And I’m not making that up. That’s a real example,” Wallace said.

“Objectivity seems like it might not be the right frame for dealing with this sort of tyrannical lying person who also specifically has it out for Muslims, Black people and trans people — and that has real consequences in terms of our lived experiences and violence and real consequences in terms of the work of being a journalist,” Wallace explained.

Wesley Lowery pointed out how the process of journalism is also inherently subjective, “no matter how much we may fetishize the idea of objectivity.” For example, there’s the dilemma about what stories to cover. Then, there are the decisions about the resources to devote to the story. You must decide how to tell the story, whom to tap as sources and so forth.

“So, the reason we have to talk about the lack of diversity and mainstream media’s bitter refusal to integrate is that when the subjective decisions are being made — on issues of race and issues of law enforcement, on issues of how much deference we provide to law enforcement or government officials — who is in the room? And who is making those decisions,” Lowery said. “And what are their politics? What are their backgrounds? What are their biases?”

Masha Gessen has been a journalist since the 1980s, when starting out in the gay press, writing about AIDS. Gessen recalls it being a formative experience that informs the perspective that journalism is a political act. “Our decisions to report or not report are inherently political,” the writer said.

Yet journalists are punished today for bringing perspective, experience and knowledge to the job. Wesley Lowrey suggested that it’s a rarity that journalists suffer repercussions because of their work; more often, it’s because of a perception that they’ve been compromised for their personal, lived experiences.

“It is always the idea that if the Republicans can prove you’re Black, well then you can’t have a newspaper job. If the Republicans can prove you’re gay, you can’t have a newspaper job. Wait, are you a woman who cares about abortion? Well, no, you can’t have a newspaper job. Over and over again, the application of this concept of objectivity [is applied to a] personal level — that our job is not to run a PR campaign to convince people that we are personally objective. I think none of us are,” Lowrey said.

“So, if we can effectively lie to our readers, we get to be journalists. And if we cannot effectively lie, then there’s no place for you in the academy of journalism,” Lowrey said.

To watch the entire, fascinating discussion, including a Q&A with the audience, check out Columbia Journalism School’s YouTube channel.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She’s reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here