To save local news organizations, Steven Waldman suggests looking to our past.

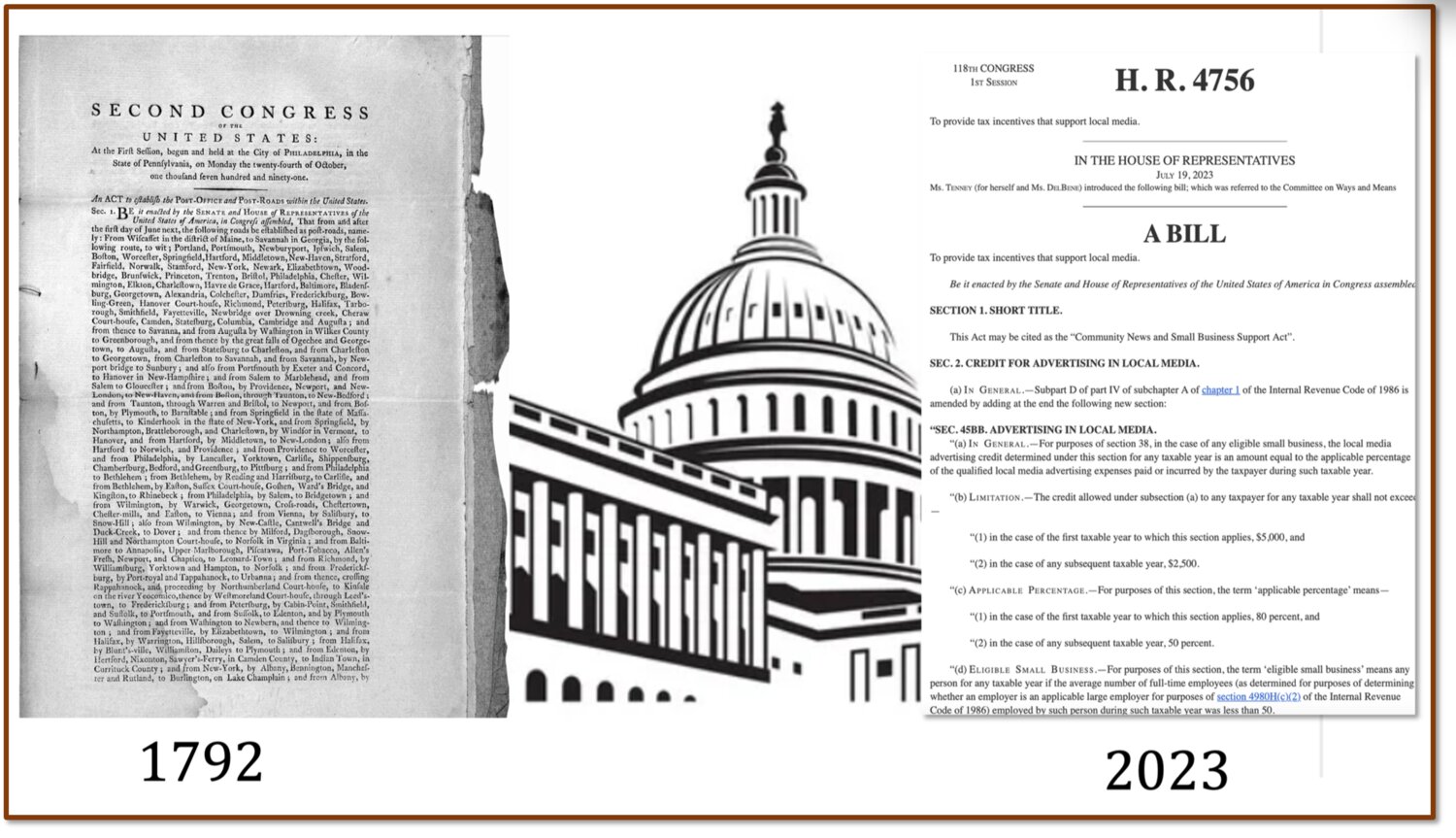

In the wake of the Revolutionary War and the birth of the United States, founding fathers like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison agreed that securing and growing a free press was essential to the country’s future. So in 1792, then-President George Washington signed into law a sweeping act that created the postal service and subsidized the delivery of newspapers.

While the cost of delivering a letter ranged from 6 cents to 25 cents, publishers would only have to pay 1 cent for newspapers to be delivered within a range of 100 miles. According to Waldman, the subsidy worked – the number of publications grew 500 percent over 30 years, from 200 in 1800 to 1,200 in 1830. Daily newspapers grew from just 24 in 1820 to 250 in 1850.

Waldman, the president of Rebuild Local News, has been on the front lines of saving local journalism for decades and thinks the lesson of government support of the news industry is extremely relevant today, as communities across the country continue to lose local news sources at an alarming rate.

“[Politics] were just as divisive as today, considering the Jeffersonians and the Hamiltonians, duels and the like,” Waldman said. “Yet they came up with a way of supporting newspapers that appeased both sides. So if they can do it, we can do it.”

Waldman is a strong supporter of The Community News & Small Business Support Act, a bipartisan bill that would once again see the federal government help subsidize local news, this time in the form of tax credits. The bill has two main components – small businesses would receive a tax credit to help pay for advertising in local news organizations, and publishers would receive a payroll tax credit for employing journalists.

Like their predecessors more than 230 years ago, the bill’s main sponsors couldn’t be any more different. Rep. Claudia Tenney, a Republican from New York, is an outspoken supporter of former President Donald Trump, who labeled outlets reporting unflattering stories about his administration “fake news.” Her colleague, Rep. Suzan DelBene, a Democrat from Washington, is a soft-spoken moderate who worked for years at companies like Microsoft before jumping to public service.

Waldman said one of the reasons the bill could be effective is it takes a lesson from the Postal Service Act. The legislation focuses on broad, objective standards rather than allowing a group of people to make subjective judgments about which news organizations to give grants to, which could exacerbate polarization and potentially lead to government manipulation of the press.

“Newspapers that the Jeffersonians hated got benefits, and so did newspapers that Federalists hated. But there was a sense of fairness that it was going to everyone with the basic qualifications,” Waldman said. “The two ideas in this new bill – a tax credit for small businesses and the payroll tax credit – do fit those neutrality standards really well.

Unfortunately, supporters of the legislation aren’t too optimistic about its chances. However, much of that is due to a dysfunctional Congress that pushes aside important public policy debates to score political points on partisan media outlets.

Polarization doesn’t help, either. 61% of Republicans say the news media is harming democracy, compared to just 23% of Democrats, according to a recent survey from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research and Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights. But these are primarily views of cable news channels and national outlets, which tend to cover politics like a horse race or sporting event. Those same respondents would likely have a different answer about their local paper’s coverage.

Waldman says the bill can still have a massive impact even if it doesn’t pass this year because it can inspire state legislatures to provide local support to news organizations on their own.

“It creates this blueprint for how to do it in a truly bipartisan way, or even in a Republican way, like in Republican legislatures,” Waldman said.

A couple of states have already taken up the call. Wisconsin has pending legislation to offer state tax credits to businesses that advertise in news publications. At the same time, there’s a push in New York on a bill that would provide a tax credit to news organizations equal to 50% of a journalist’s salary in the first year, capped at $50,000 a year. That bill would also give subscribers a tax credit of up to $250 annually.

“Local journalism is as much of a benchmark for our communities as a school or grocery store is," Assemblyman Steve Hawley, a Republican who supports the legislation, said in a statement. “Help from the state to maintain these institutions is critical as it saves jobs and preserves a community's identity.”

Other states are taking different approaches. California, New Mexico and Washington subsidize reporters' salaries to put them in local newsrooms. In Connecticut, the state Assembly passed legislation requiring half the money the state spends on advertising to go to locally-owned media companies. New York City has a similar requirement, which has funneled about $25 million over two years to local newsrooms, according to the Craig Newmark Center for Community Media.

In New York, the bill to provide tax credits is being supported by both news organizations and unions, a far cry from a time when journalists feared the influence of government funding on their reporting. In fact, journalists have a solid case to make that small state and federal investments in news gathering can save their local communities tens of thousands of dollars.

A 2022 study by Northwestern University’s Medill School showed that in communities without a credible local source of news, residents ended up paying more in taxes and in the checkout line, thanks to unchecked increases in corruption “in both government and business.”

One of the most famous cases happened in 2010 in Bell, California, a working-class suburb of Los Angeles, where the city manager and other municipal officials enriched themselves using millions of dollars of taxpayer funds. The scheme was perpetrated in the open during public meetings, but with no local reporters covering the town, it went unchecked for 17 years before being exposed by the Los Angeles Times.

“This is the thing you do. You go to a council meeting, you sit there, you try not to fall asleep, and you pay attention to what’s being approved, what’s being said by the residents,” Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Vives, part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for exposing the scandal, told NPR in 2010. “Someone would’ve gotten wind of this earlier had a reporter been there.”

In a recent piece in The Atlantic, Waldman rounded up several cases where journalists saved towns and residents considerable money. In just one case, Zak Podmore – then a reporter for the Salt Lake Tribune – uncovered that a law firm had, among other things, overcharged a poor Utah county by $109,500. Due to the story, the firm paid the county the money back.

Podmore was only able to cover rural San Juan County thanks to Report for America, a nonprofit Waldman founded that funds the placement of young journalists into newsrooms to cover issues that have been neglected or overlooked due to shrinking newsrooms. As Waldman noted, Podmore saved the county triple his annual salary with a single story.

“We haven’t really been making the argument about saving money in a direct way because we didn’t need to in previous years,” Waldman said, alluding to when news organizations were flush with cash. “We’ve kind of neglected this argument because it’s less highfalutin, but it may be more persuasive to everyone, including donors, policymakers, and voters.”

Rob Tornoe is a cartoonist and columnist for Editor and Publisher, where he writes about trends in digital media. He is also a digital editor and writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Reach him at robtornoe@gmail.com.

Rob Tornoe is a cartoonist and columnist for Editor and Publisher, where he writes about trends in digital media. He is also a digital editor and writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Reach him at robtornoe@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here