While the first saturation-coverage war in years unfolds in Europe, many may look to journalists with military backgrounds for context grounded in experience. Yet the ranks of vets in the U.S. media are thin. Around 7 percent of Americans have served in the armed forces. Still, only 2 percent of media workers are veterans, according to a Census data analysis from Military Vets in Journalism (MVJ), a group founded in 2019 with a mission to attract more veterans to the industry. Veterans haven’t flocked to the field despite their proximity to current events and the developed skill sets and specialized knowledge many possess.

Journalism is a challenging field to break into is a common refrain from veterans moving into and already ensconced in the U.S. media. “There was a time where I didn’t want to be a journalist because I was getting people saying it’s hard to get into and it’s cutthroat,” says Altasia Johnson, a former Air Force sergeant now building a career in journalism.

“Journalism is a really hard field to break into no matter who you are,” says MVJ co-founder and president Russell Midori, a former Marine. “It’s a professional job that pays low, especially in the beginning, and it costs a lot of money to build the degrees and what you need to build bona fides in the industry.”

The U.S. Army pays its employees an average of $64,000 a year. The Marine Corps is at $52,000, the Navy is at $69,000, the Air Force is at $65,000 and the Coast Guard average base salary is $77,000, according to PayScale. The average salary for a journalist is $41,000.

“I think a lot of times, veterans just give up and say, ‘Well, I’ll become a cop, where my skills are valued,’ or ‘I’ll go do another job where I can at least start at $50,000 a year and have a 401(k),’” said Midori.

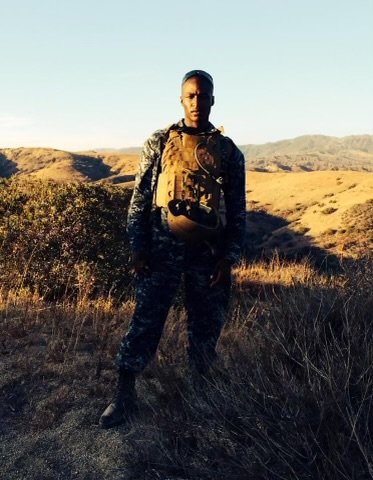

In Johnson’s case, she couldn’t turn away. “This is the only thing that I’ve ever been passionate about or ever wanted to do. So I’m fully invested. Now I can’t go back.” After two deployments to Afghanistan, where she worked as an executive assistant, she’s now getting a bachelor's degree in journalism at the University of South Carolina. She’s also working as an analyst for Huntington Ingalls at Shaw Air Force Base outside Sumter, South Carolina. Johnson has done freelance work for the North Carolina National Guard Association, the Tarheel Guardsman magazine and AmeriForce Media for their Reserve & National Guard Magazine. She’s interested in on-camera reporting.

That passion for journalism is reflected among others who served. Like many in the media, these vets carry a feeling of doing something significant, of pursuing a calling.

Lucretia Cunningham is among those who long dreamt of a journalism career. Cunningham was an Air Force medic for 10 years and trained as an allergy and immunology technician. But she found it hard to make rank in that specialty, heavily reliant on the flu season as the “big show.” In 2016 she got an ultimatum from the Air Force: either get out or train for flight medicine. She got out of active duty and went into the Air National Guard, lingering in the medical field.

“I figured ‘I'll go to nursing school,’ even though I didn’t even want to work in a hospital. I think I was watching a documentary or something about a reporter. And I was like, what would it take for me to just do that?” She decided to cross-train as a journalist and studied at the Defense Information School (DINFOS) at Fort Meade, Maryland. She used the GI Bill to get a bachelor’s in communications from Old Dominion.

On Facebook, she found Military Veterans in Journalism and the group connected her with mentor Alex Sanz, deputy director of newsgathering at The Associated Press. They trained remotely, with phone calls once or twice a month. “To talk about what I was doing, what I was working on. How I could make my stories better or the goals that I had.”

After being featured in an MVJ event, Cunningham landed a job in 2021 as a reporter with KUNR public radio in Reno, Nevada. She’s also working as a public affairs specialist for the 926th Wing, an Air Force Reserve unit.

Journalism represents a way forward for New York-based Jordan Sartor-Francis after being medically discharged from the Navy in 2018. A graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he planned to remain in the Navy for at least five years, perhaps as long as two decades. Casting around for a post-Navy career, he found himself unsure. He did some modeling and acting, going from gig to gig. He then Googled veterans in journalism and found MVJ. “Oh, this is perfect,” he thought.

MVJ connected him with mentor Lynn Smith, who had a 15-year career as an anchor on NBC News, MSNBC and CNN Headline News, and launched consulting firm Rylan Media. “I think I would probably be just sitting in bed all day, dreaming about becoming a journalist instead of actually taking steps to do so if it weren't for Russell and Military Veterans in Journalism,” said Sartor-Francis.

Sartor-Francis, targeting a career in broadcasting, plans to go to grad school at CUNY’s Craig Newmark school.

Why so few?

Why are so few vets in the media? “It's hard to say for sure,” said Sam Kille, former Marine and spokesman for New York-based nonprofit Report for America (RFA), which places journalists into local newsrooms with a stated mission to report on under-covered issues and communities. “Especially when you consider that a lot of military veterans do tend to gravitate towards jobs that have some kind of service component to them.”

“I think military vets find it difficult to transition to any job when they leave the military. Among big challenges that they face: they might be older, and they may have less education than some of their peers,” he said. “The problems with journalism itself can make that even more difficult,” he said, citing the often low pay and barriers to entry.

Since launching in 2017, RFA, co-founded by GroundTruth Project CEO Charles Sennott and journalist/entrepreneur Steven Waldman, has seen 385 journalists chosen for newsroom positions. Twenty-seven veterans have applied to the program since the group began tracking veteran status two years ago, while five U.S. military veterans and one Israeli vet have gone into the reporting corps. “This, of course, is less than 2% of our corps to date, and we would like to see this number grow,” says Kille.

Kille points out that RFA doesn’t make the final decision on the hiring of any of the members of its corps. RFA pays about half their salary, with the other half covered by local news outfits with help from local donors.

RFA recently called for more veterans to apply to its journalistic corps in a post titled “Report for America seeks military veterans.” The group is working with MVJ on the effort.

Major, sergeant-major

It’s not hard to identify the value military experience brings to news. Beyond the obvious — knowledge of equipment, operations and “being the only journalist in a newsroom who knows the difference between a major and a sergeant major,” in the words of Russell Midori. Johnson, Sartor-Francis and others said that military experience can foster a self-direction that civilians may not associate with top-down operations such as the armed forces. “Start with independence. Being able to do things on your own without having anybody tell you how to carry it out to your best ability because that's kind of ingrained in us. You don't need full directions to know how to get the job done,” says Anthony Vazquez, a Marine vet who worked as a landing support specialist and is now a photojournalist with the Chicago Sun-Times, a job he got through RFA.

Vazquez, who spent more than two years as an Associated Press stringer in Mexico City, also cites communication. “In the military, you have to have great communication, especially if you're not speaking to somebody in your own branch.”

Talking to people around Chicago communities struggling with gun violence, Vazquez draws on his two deployments in Afghanistan and “knowing what PTSD is and what they’re going through because you have friends and others who have dealt with it in the military.” Having that knowledge equips him to connect a bit more, he said.

Cunningham, who reports on general assignments along with military-related material, believes her military experience is useful to KUNR in part because she knows who to contact. “I'm working on a story right now about the Guard working in non-traditional roles, supplementing the workforce with struggles that we’re having,” she says.

“They are resourceful; they're excellent problem solvers. They kind of have a healthy distrust of the government,” says Midori of veterans. They can be hardy, he adds. But Midori is hesitant to characterize vets given the lack of uniformity in their experience and outlook. “Veterans are valuable to newsrooms for the same reason that people of different ages are valuable to newsrooms and people of different racial backgrounds or different religious backgrounds. It's really about diversity, and they bring a diversity of experience.”

In the Military City

Many would agree that one doesn't have to be a vet to be a solid military reporter, nor should vets be pigeon-holed to cover war or military issues. Johnson, for example, would like to cover military or vegan/vegetarian food trends.

One who provides a rare level of military affairs insight at the local level is retired Air Force officer Brandon Lingle, who secured a job at the San Antonio Express-News through RFA and now sits on the editorial board.

Lingle dedicated 20 years to the Air Force, primarily working in public affairs after receiving training at DINFOS. He retired in 2020 as a lieutenant colonel. He writes in a city that hosts Joint Base San Antonio, a city so dedicated to a military identity that in 2017, it registered a trademark for the moniker “Military City USA.” The paper has a longtime military reporter, Sig Christenson, and Publisher Mark Medici was interested in adding a voice with military experience to the editorial board, says Lingle.

“I’ve found myself increasingly frustrated with the lack of transparency from the military, at least in my time in this position on the opinion side. A lot of FOIAs (Freedom of Information Act requests),” says Lingle. He says the Defense Department stripped away information going back to 2014 that had been public on defense.gov, in an effort, Lingle posits, to protect Afghans who worked with the U.S. He brought attention to the scrub-out in a piece headlined “In purging archive, DOD transparency takes a step back.”

“I still have contacts and lots of sources. But I'm outside of the institution now, so I don’t have the insider knowledge and tools available to me that I did when I was still in the military. There have been times where it’s been hard.” Nevertheless, Lingle manages to spotlight topics that don't typically get much sophisticated coverage in the non-military press.

The first time he reached back to people he knows in the military was for a February story titled “An Air Force senior general just got candid about mental health in the military.” Lingle had worked with that general in the past, and he was very open to having the conversation, said Lingle. “It was his first media engagement since taking command in October, so I thought that was really cool that he was willing to talk with me and trusted me with his story.”

The story reads: “Gen. Mike ‘Mini’ Minihan, who is responsible for about 107,000 people and nearly 1,100 of the military’s cargo and refueling aircraft, tweeted a photo of his schedule that showed an upcoming mental health appointment with the words ‘Warrior heart. No Stigma.’”

Lingle also recently wrote on the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. “I was able to, on the column and opinion side, have a little bit more leeway than on the hard news side. I was able to incorporate some more literary approaches to talking about Afghanistan, whether that’s weaving in memories or other stories from my experience there and using that as a filter to look at what’s happening now.”

Lingle’s February article, “Ukraine’s story may inspire; still, it’s one of horror,” addressed the war in Ukraine. “We don’t understand the war in Ukraine,” it read. “We should keep a healthy skepticism of government statements and bold headlines. They may be factual. They may be grounded in fact and embellished. They may be false but emotionally true. They may be nonsense. Each may be true in its own way. We need to be smart consumers of the information and realize each bit that trickles onto our screens may be trying to manipulate us,” he wrote.

He has also been looking into trends concerning embedded reporters, saying that the military embedding practice has faded over the years. The issue has come to the fore. The Military Reporters & Editors Association is calling for the resumption of embeds. It is lobbying the DOD to allow journalists to embed with U.S. troops chosen to deploy to NATO’s eastern flank, according to a Feb. 6 press release from the group.

The Express-News editorial board also had a March piece concerning a fatal crash of two T-38C Talon training jets at Laughlin Air Force Base near Del Rio, Texas. They have called for the end of Operation Lone Star, Gov. Greg Abbott’s border security mission that has mobilized thousands of Texas National Guard members.

“The veteran and military community is not a monolith,” said Lingle, reflecting on his approach. “There is the classic narrative of the broken veteran and struggling veteran. I’m more interested in the stories of veterans who are stepping up to challenges and living with their past and growing and becoming stronger and more resilient.”

“Journalism needs veterans more than veterans need journalism,” declares Russell Midori, president of Military Veterans in Journalism. The professional association, launched in 2019, has gotten mentors for hundreds of people, gotten people fellowships and gotten people jobs. It’s a busy group.

“But as we’ve grown, we’ve seen ways that our work is providing a service to journalism itself, not just veterans. The media is widely distrusted by a growing number of Americans right now. And veterans’ reputation for selfless service is one of the ways that we can help restore public trust in the news,” said MVJ co-founder Midori, a former Marine with a master's degree in journalism from Columbia who works as a photojournalist for WPIX Channel 11 in New York.

“The number of veterans that we have working in news media is out of step with the number of veterans in the audience, and that’s inherently bad for journalism. And it’s inherently bad for freedom of speech,” Midori told E&P. Midori sees the gap in veteran representation as especially wide in newsroom leadership.

Most of MVJ’s funding comes from grants, including the Knight Foundation, Craig Newmark Philanthropies and the Wyncote Foundation. The nonprofit association, which Midori says has 500-plus members, has recently gotten grants from the Ford Foundation and News Corp Giving.

With the News Corp grant, MVJ plans to provide, via an online portal, standards and guidance for reporters covering military issues. As part of the grant, MVJ is also developing a style guide along the lines of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists’ Cultural Competence Handbook, published in 2020.

“Our community of military veterans in journalism has deep and personal knowledge of the issues affecting the military and veteran communities. We want to share our expertise and best practices with other journalists doing reporting on these issues, hopefully leading to stronger and more nuanced news coverage across the nation,” said co-founder Zack Baddorf, MVJ’s executive director and a Navy veteran.

A stronger understanding of all aspects of military life and nuance is needed in coverage on topics such as PTS/PTSD and military sexual trauma, said Baddorf. “More simply, reporters mix up military terminology, like ‘commander’ and ‘officer,’” according to Baddorf.

Also in the works is a subject matter experts directory. The style guide and experts directory are due to launch through the portal on Veterans Day — Nov. 11, 2022.

The $200,000 Ford Foundation grant aims to improve news coverage of disabled vets. In partnership with Disabled American Veterans and the Disability Media Alliance Project, MVJ is launching a speakers bureau and will train eight military veterans on best practices in disability reporting. The veterans will go on to do their own training and presentations in local newsrooms. The program got more than two dozen applications.

The group has established fellowship programs with outlets such as CNN, The Washington Post, Task & Purpose and Military Times. Also among MVJ initiatives: developing a web portal for job seekers, holding a 2022 in-person convention in Washington (likely in early October) and producing a podcast, Sword and Pen. MVJ is working to expand its services to vets who aren’t members, says Midori.

Early adopter

One who was an MVJ member from the beginning is Dustin Jones, a former Marine who completed tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Jones, who knew Midori as a fellow alumnus of a documentary program at Columbia, was the first Military Veterans in Journalism intern at NPR in 2020. “I had been working at Home Depot for four or five months leading up to that because that was the only job I could find. I was working overnights unloading tractor-trailer trucks and stocking shelves 9 p.m. to 6 a.m.” He interned as a producer for All Things Considered and a reporter for the Newsdesk.

There were more than 20,000 applicants for fewer than 30 NPR internships in fall 2020. “Instead of having to compete against those kinds of numbers, I applied for the MVJ internship, which was one slot, but my chances were one in 35 or one in 40.”

Jones, operating out of Southern California, is currently on-call for NPR and writes full-time for Black Rifle Coffee’s Coffee or Die magazine, aimed at military vets, first responders and coffee lovers.

“The fact is that it will take a very long time before the industry truly recognizes veterans as a community worthy of inclusion in editorial decision making,” Midori said. “I don’t know if we’ll ever see veterans represented in newsrooms at the same rate they are present within our population, but at least through these grants, we can help them to punch above their weight in terms of newsroom influence.”

Mary Reardon is a writer and editor based in Wisconsin.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here