On June 24, 1988, The New York Times reported with an A1 headline: “Global warming has begun.”

The day before, in an alarmingly hot summer in Washington, D.C., then-NASA climate scientist Dr. James Hansen testified in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Energy and Natural Resources. He presented the case that the climate was warming and that it resulted from human activity. This testimony is considered the first time global warming has become an issue of public interest in the United States and, therefore, a slow but growing priority for news coverage.

For early climate journalists, covering such a serious issue was a burden. Not many publications wanted to take on the task at hand; those who did narrowly covered a small amount of ground. Dr. Edward Maibach, the director of Mason’s Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, said there was also a major faux pas with some early reporting practices.

“Many journalists who reported on climate change in the past felt the need to tell both sides of the story, when in fact, there really was only one side of the science — the evidence — of what’s happening,” said Maibach.

Although necessary in certain circumstances, this reporting tactic is not an ideal approach to covering climate change and can lead to confusion in the public sphere.

“To go out and seek out voices who are contrarian voices but aren’t fundamentally actually focused on things that are happening in the real world — they’re focusing on interpretations that they want us to believe — that was a real mistake. It’s not ‘fair and balanced’ when you present both sides, and there’s really only one side that’s fundamentally true, based on evidence. That’s called false balance,” said Maibach.

Over the years, that approach has diminished, but there is still room for improvement.

“Focus not only on the impacts that are already happening in our community but tell stories about what people are doing about it. That’s what audiences are really most interested in,” Maibach suggested.

Maibach draws this conclusion from his 40 years of research experience studying public communication campaigns. He cites a simple formula that can translate to storytelling: “Clear messages repeated often by a variety of trusted and caring voices, including familiar TV weathercasters or local columnists.”

“Their viewers know them; their viewers like them, and their viewers trust them. And so, when they talk about the ways in which climate change is changing the weather conditions in their community, people don’t talk back, people don’t argue with that,” said Maibach.

Maibach believes it’s the local voices that can help educate communities. One example of a local voice who led the charge of climate reporting is John Morales. He was the first hurricane specialist at WTVJ NBC-6 in Miami. He founded and leads ClimaData, a boutique forensic meteorology firm. He leaned into climate coverage 25 years ago after being a part of a group of TV weathercasters invited to the White House.

“We met with scientists from NOAA and whatnot. We met with policymakers, as well. … In the evening, we were in the East Room of the White House, and there was a reception with the president and vice president. They both gave speeches. The vice president’s speech was like watching ‘An Inconvenient Truth,’ but in person. I personally left that event inspired because all they were asking us, as broadcast meteorologists, to do was to try to include some climate context in our reporting,” said Morales.

“I’m an atmospheric scientist by training. I had been reading the papers; there was nothing wrong with science from my point of view,” he said. But he faced a few issues in the beginning.

“The problem was that I worked in Spanish-language TV. … They not only provide local news, but they try to sprinkle in news from all the different countries. So, when you have a rundown that includes a story count that is that high, there's not a lot of time left for weather,” said Morales.

Morales found a solution. He separated his climate coverage away from the weekday forecasts. He did longer reports for the news in a separate format called “packages,” which is a story ranging from 90 seconds to 2.5 minutes. In 2003, he began reporting for a Telemundo station and doing some crossover work for an NBC station.

“And at the same time, weather extremes were starting to ramp up just a bit. … More opportunities were starting to arise for me to do some more of those longer-format type of reports. If I could sprinkle some climate context in a weather segment in the Telemundo station, I would,” he recalled.

Morales communicated the message effectively, avoiding scare tactics and centering his reporting on local concerns.

“We were seeing more rainwater runoff type of flooding going on, not just in South Florida, but in other parts of the state,” said Morales. These events allowed him to also talk about climate.

“Sea level rise was accelerating in our area. We’ve seen 6 inches of sea level rise in just 25 years, which is a lot faster than much of the rest of the world. So, all I would do is talk about these different climate stories,” said Morales.

There was pushback at the beginning, particularly from management. Morales was told to find “two sides” to his climate story, a practice he didn’t see as relevant to climate reporting.

“Science doesn’t work like that. The scientific method doesn’t give you two sides to the story,” said Morales.

Externally, Morales said he didn’t see much public pushback.

“Yes, on social media, you do get some of that. And the trend, by the way, that I’ve observed is less pushback in the present day as compared to 10 or 15 years ago,” said Morales.

“If you casually ran into somebody at the hardware store, or you know, at the supermarket, and people struck up a conversation with you, they would say, ‘Oh, by the way, thank you for being the only one in Miami that talks about climate, because gosh, I mean, we’re ground zero, and nobody wants to talk about it, but you’re talking about it,’” he said.

As for climate reporting, Morales has a few tips on how to get started. If there’s a climate angle to a story, include it. Communicate with straightforward language that non-scientists can digest. Use layman’s terms, and try to relate to readers on a local level.

Morales said in his experience, strong climate reporting can attract reporters to newsrooms, citing a colleague, Steve MacLaughlin. McLaughlin was a meteorologist in Florida who came to work for the station because he was encouraged by the long-form climate coverage.

Although meteorologists are an excellent example of reporters reporting on climate, smaller newsrooms can utilize general assignment reporters to bring the story to the audience. Frank Mungeam is the chief innovation officer at the Local Media Association. He leads the Covering Climate Collaborative, a network of 25 local newsrooms and six science partners reporting on the effects of climate change, climate justice and climate solutions.

“Climate really is in everything that we do. It’s a health story. It’s a transportation story. It’s an economy and jobs story,” Mungeam said.

“The effects of climate change have been disproportionately experienced by underrepresented communities, and so the legacy of where the worst climate impacts have occurred overlaps with housing injustice and political access inequities. The folks who haven’t had a seat at the table, who haven’t had a strong voice in shaping policy, citing where factories and plants and waste go, no surprise, have turned out to be unequally impacted,” said Mungeam.

He suggested that climate reporters need to move beyond “problem and documentation reporting” and incorporate solutions journalism in their practice.

“The data is pretty clear that people know we have a problem. … The effect of solutions reporting is to give communities and individuals agency and a clear idea not only of what the problems are but what can be done about those problems,” Mungeam explained.

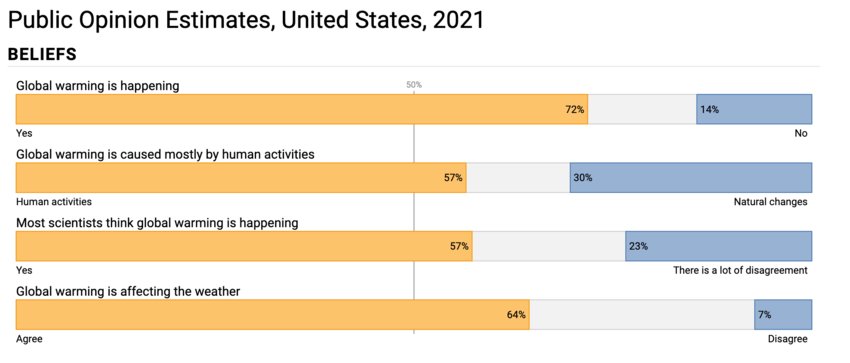

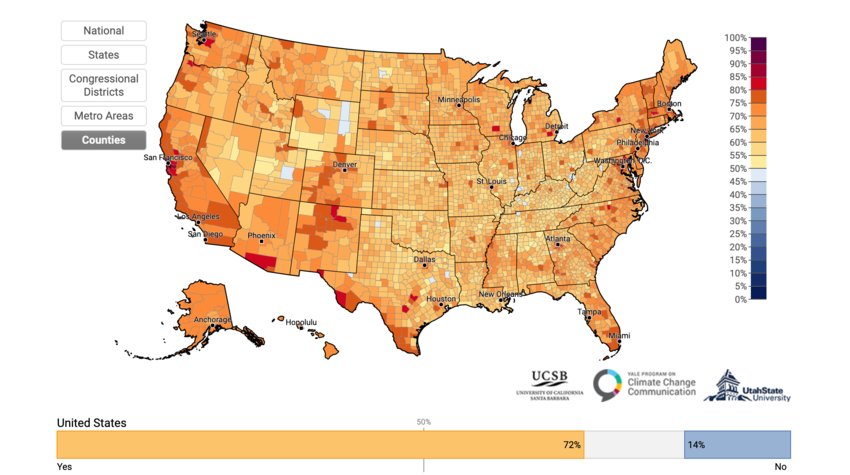

Mungeam referenced data from Yale Climate Opinion Maps, which shows Americans’ climate change beliefs, risk perceptions and policy support at various governmental levels, such as by county, state and congressional district. Mungeam also invited newsrooms to tap into the Covering Climate Collaborative.

The Collaborative has worked with a number of journalists and news organizations to amplify climate coverage and make connections between newsrooms for joint storytelling opportunities. The organization also provides mentorships and hosts a wealth of storytelling ideas. Although there are challenges for newsrooms, big and small alike, Mungeam has a positive outlook on the nature of the industry and its ability to adapt.

“These are all the things that journalists do well — filter complex issues, synthesize them and report out in a trustworthy way,” said Mungeam.

Victoria Holmes is a freelance journalist and writer based out of Dallas, Texas. Previously, Holmes worked as a TV news reporter and political podcast host at WNCT-TV in Greenville, North Carolina. Reach out to her on Twitter.

Victoria Holmes is a freelance journalist and writer based out of Dallas, Texas. Previously, Holmes worked as a TV news reporter and political podcast host at WNCT-TV in Greenville, North Carolina. Reach out to her on Twitter.

1 comment on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here

enigma58

>>...“Focus not only on the impacts that are already happening in our community but tell stories about what people are doing about it. That’s what audiences are really most interested in...<<

Actually, the audience is not really interested in either of these options. The simple fact is that climate is not a local news story. Local reporters cover events. Interpreting those events as to whether they validate a particular scientific construct, or support a social or political agenda is outside the scope of local reporting. Fire in an apartment building is not the starting point for a discussion of fire safety regulations. A heat wave is not a starting point for a discussion about drought.

Reporting local news means sticking to the facts, and just the facts...and as many as possible. The idea that it is somehow the local reporters' job to advocate for this or any other social/political cause is what is dooming journalism's credibility with the readers/viewers. Let columnists and politicians make the "big picture" pronouncements and bend the facts to fit their narrative. It's what they are paid for. The local reporter is paid to relate only what is demonstrably so, and only to the extent it is demonstrably so. Nothing more, ever.

Tuesday, October 25, 2022 Report this